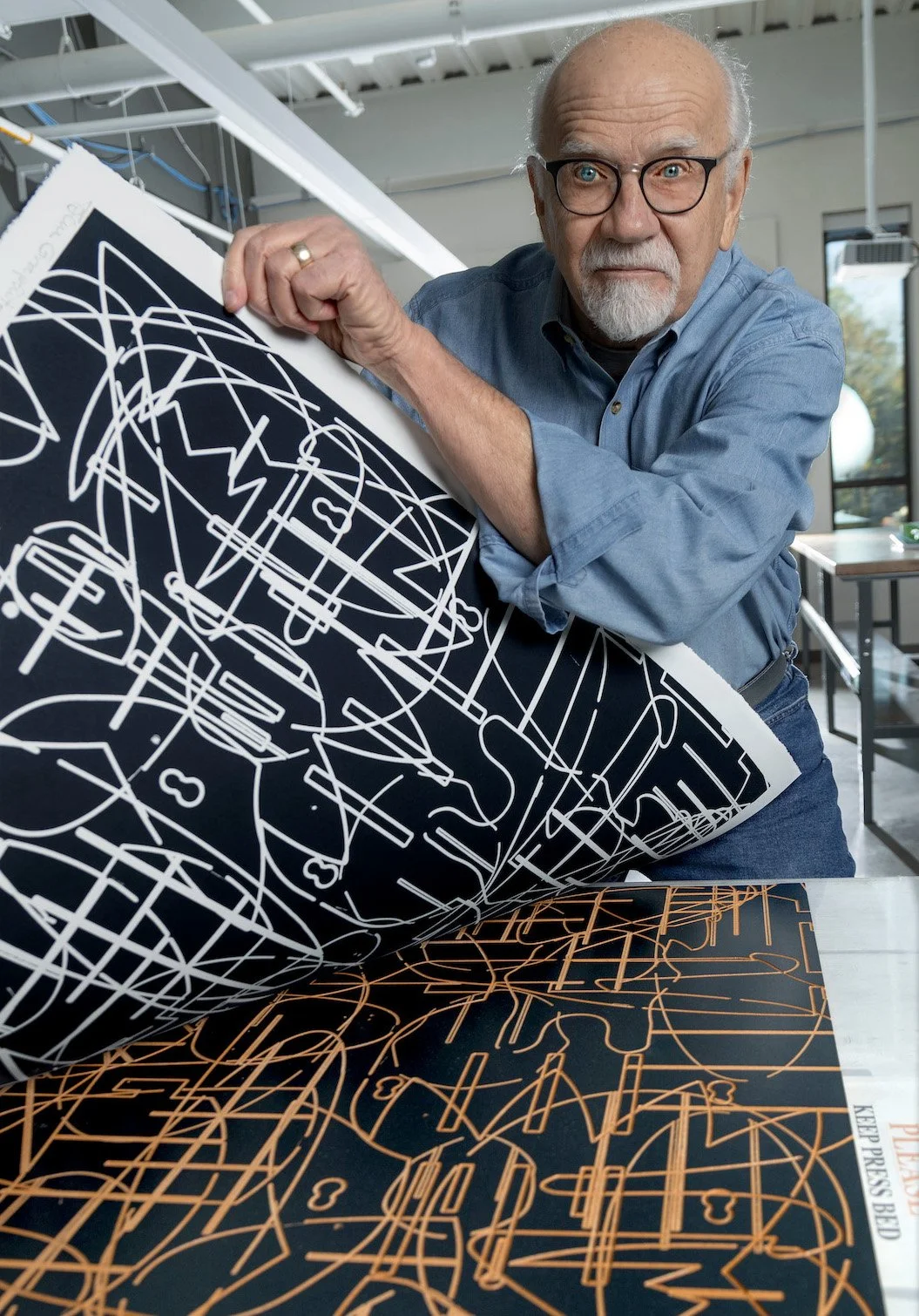

Interview with artist L.S. Eldridge

L.S. Eldridge is a representational watercolorist living in Rogers, Arkansas. She is a Signature Member of many watercolor societies including the American Watercolor Society, National Watercolor Society, Transparent Watercolor Society of America, Artists of Northwest Arkansas, and is a Diamond Signature Member of the Mid-Southern Watercolorists. Her extraordinary paintings have earned national and international acclaim and are in numerous private and museum collections. More of L.S.’s work can be found at the Galleries at Library Square in Little Rock, and at her website lseldridge.com.

AAS: Tell me about your background. Are you originally from Arkansas?

LSE: I’m not originally from Arkansas. My father was an USAF Officer, and it was routine to move every few years. After he retired from the military we settled here.

AAS: Where did you study art?

LSE: The truth is that I have been studying and pursuing art since I was three years old. My parents told me I was an artist and I believed them. My teachers from kindergarten forward told me the same. My high school counselor recognized my interest in art and math and encouraged me to take mechanical drawing. I had a great teacher and truly enjoyed it. I pursued it in college as well, but my main interest was always the fine arts. It certainly helped with proportion in my drawing skills! To this day I still use my high school drafting set.

I studied art and journalism at the University of Central Arkansas. Unfortunately, I only lacked three hours to graduate and just ran out of time. I came back a few years later, but they had dropped my particular degree and informed me I would have to start over. I wasn’t able to do that, so I use the education I received and lack the paper. I am grateful for the marvelous art professors I had that taught me a genuine work ethic in which to create art. I also had an interest in needle arts and was fortunate to meet Martha Pullen. She saw my designs and immediately asked me to start designing and writing for her magazine Sew Beautiful. That is how I began my work as a freelance designer and technical writer. I continued this course until both my children were older and I finally decided to pursue painting full time. I continued my painting education through workshops with contemporary artists and always strive to expand my skills.

AAS: So, art was a big part of your life growing up?

LSE: My parents had respect for the arts and sciences. It wasn’t unusual to travel to see a certain museum or see an exhibit. When I was very young my parents saw an exhibition of Picasso’s work. On their return they had us kids do a finger painting and my father made frames for them. Those paintings were hung with pride in our many homes. The point being they believed that art wasn’t limited to just a few, it was a vehicle for expression. I still have my painting. Hmmm…I would definitely call it abstract expressionism.

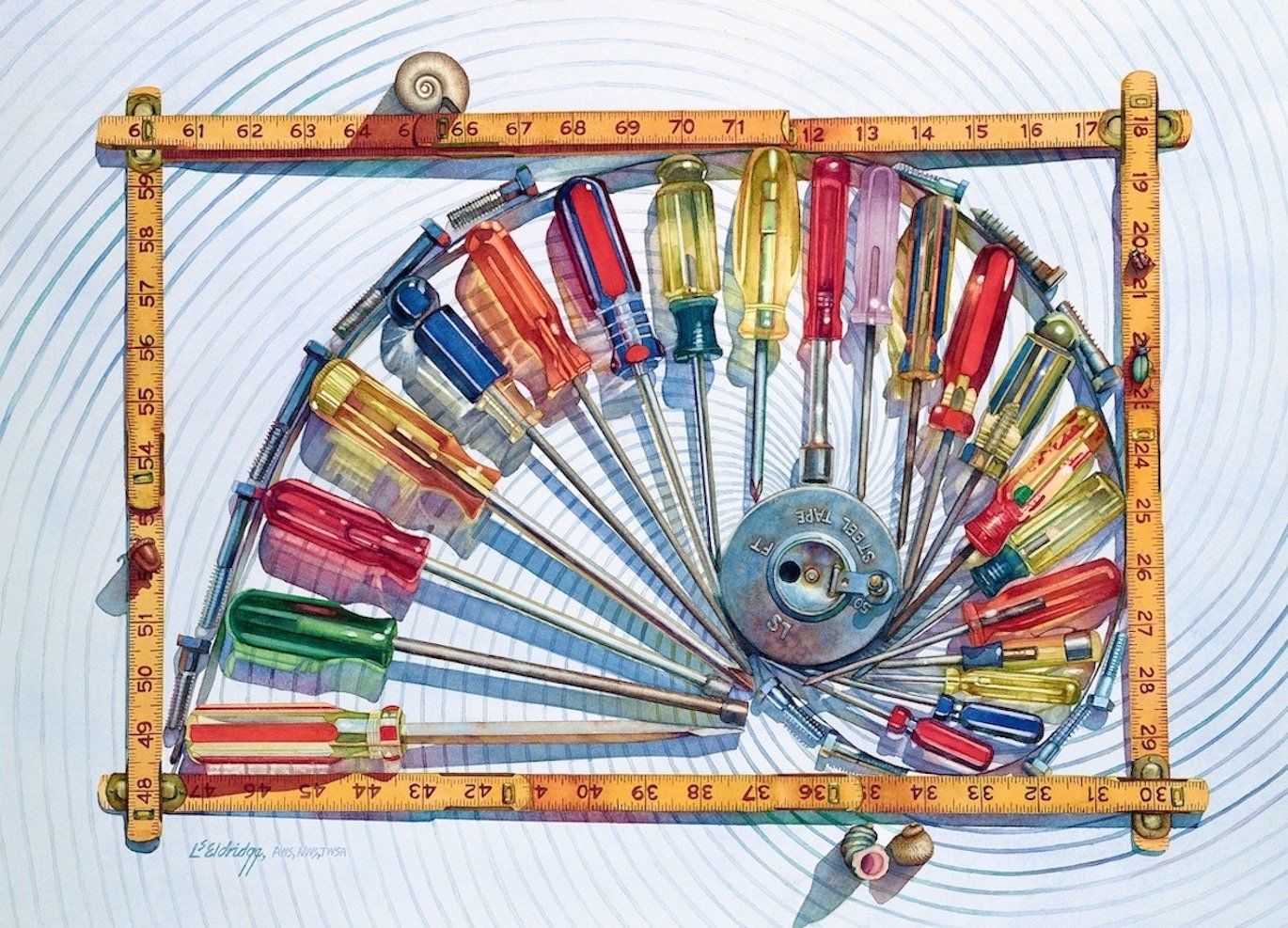

AAS: I first saw your marvelous watercolors at the Galleries at Library Square. What really struck me were the bright colors and rather unusual choices of subjects. A Measured Response is a good example of what attracted me to your work. Would you talk about that piece? I know it won the Mid-South Watercolorists President’s Award in 2019.

A Measured Response, 27” x 25”, transparent watercolor

LSE: A Measured Response is part of my “Measure” series of paintings. This series started as a memorial to a small barn on family property that had flooded so many times it had to be demolished. We relocated regularly when I was growing up, so to me this property felt like “home”. I was offered the barnwood to make frames, but instead I chose these discarded tools left abandoned in a drawer. As I held them up to the light, a flood of emotions overcame me and I knew that these jewel-hued treasures held the spirit of this place. They would tell the story of loss and longing. But how? Through color. Loss is such a sharp emotion. The only way to depict it is with really bright colors. I once read that Mark Rothko said color was depressing. I get that, but I describe it a little differently. If I am dealing with a deep emotion, color is the only thing I can depend on to lift my spirits. Though the tools are not as they appear now all faded and scratched, the memories are vivid. Thus, I portray the tools as practically new. The background is a depiction of wood grain implying the timber, or character of the barn. Does this particular painting have a message? Yes, it is plainly visible. When I choose my subject matter, like poetry, it must be able to have more than one meaning. I am a watercolorist, so I layer my work in every regard. I am a watercolorist and I have experienced both the beautiful nature of water and its destructive force. Unfortunately, the loss didn’t end there because the home eventually had to be demolished as well. I did a small painting titled The Patterns of Home to commemorate that fact which is now owned by the Arkansas Department of Heritage. The painting depicts a lush lone path, but for me the reality is that the pathway goes nowhere. This series is wonderfully cathartic. Eventually I had an epiphany when I realized that I couldn’t think of anything that wasn’t a tool. At that point I knew the tools could be used to portray or address anything. I moved them, and myself forward and have used them to portray anything from the tools of art to the problems of climate change.

The Patterns of Home, 15” x 15”, watercolor

AAS: Your work is representational and often very realistic, and your training in mechanical drawing comes through. But I think it is your depiction of light that makes your work so unique.

LSE: Well light and shadow go hand-in-hand. I portray light by using surprisingly colorful shadows. I taught my own children in this way: What color is a tire? They told me tires were black. I told them there was no such thing as a black tire. They scoffed. I proved them wrong. Now they see color where before there was flatness. Now they understand and have no fear of color.

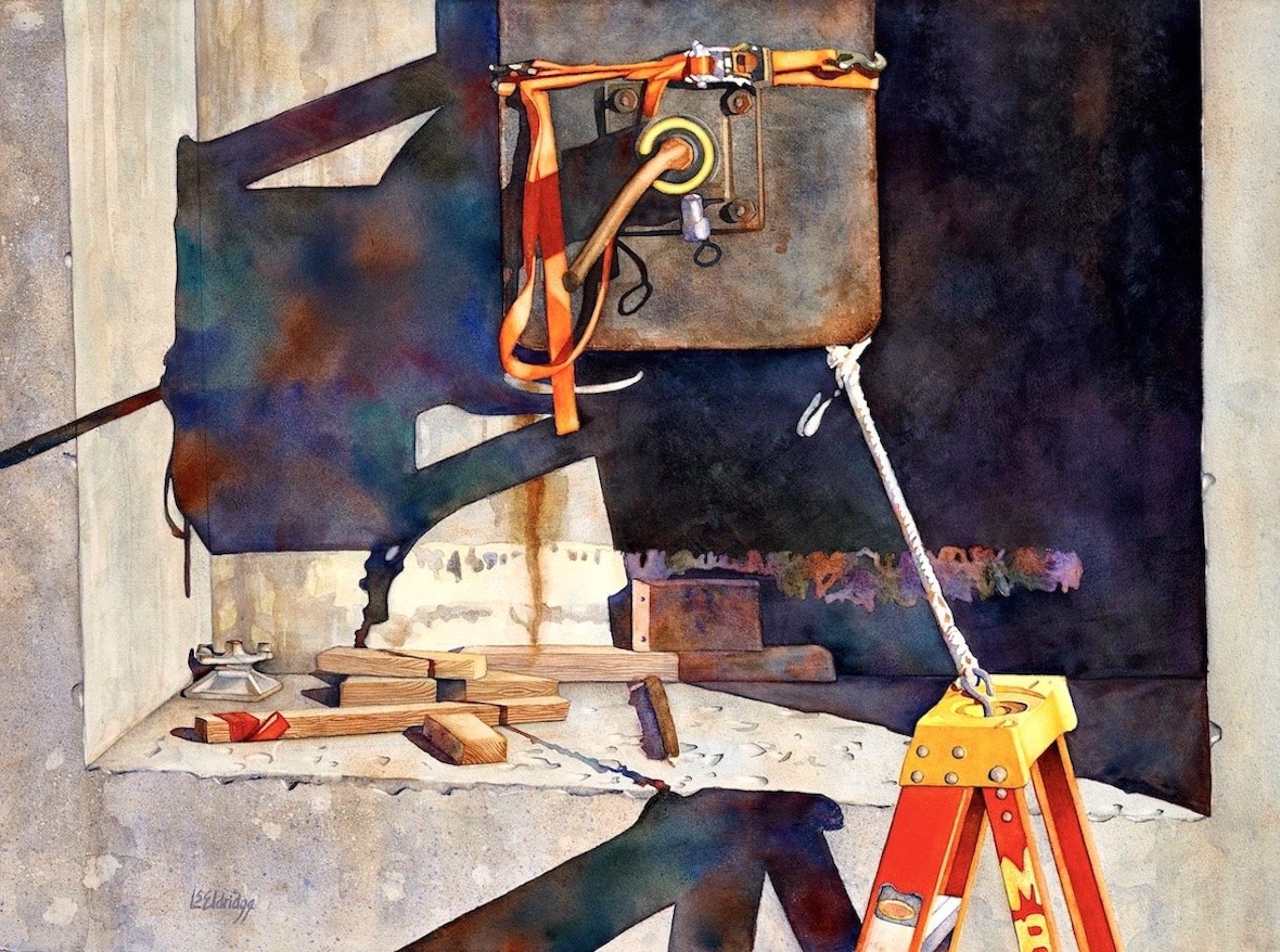

AAS: I think Sticks and Stones is a great example of your use of light. It is currently on exhibit at the Watercolor USA Exhibition at the Springfield Art Museum. Tell me about that piece and the exhibition.

Sticks and Stones, 22” x 16”, transparent watercolor

LSE: I have great regard for the Springfield Art Museum. They routinely invest in current watercolor paintings for their collection. They allow out-of-norm paintings and ideas. I regularly submit and am always delighted when my work is included. If you have the opportunity you should visit their exhibits.

I am devoted to watercolor as my medium because, no matter the style or subject matter, I am always drawn to its translucent beauty. This painting is part of a series addressing climate migration. In Sticks and Stones, I explore the rigors of climate migration and what precipitates such an exodus. The changing weather impacts the rivers, oceans, animals, plants and everything around us. In this particular scenario drought is the key component. Here on the drying riverbed, we are reminded that all things are connected. The stories of my Choctaw ancestors speak of a partnership with the land - listening to the signals from nature and acting on that information. My eyes and ears are open.

“I am devoted to watercolor as my medium because, no matter the style or subject matter, I am always drawn to its translucent beauty.”

AAS: What is it about rendering such detail in your paintings that excites you? Is it simply the technical challenge?

LSE: I admire clarity. I used to paint in a very loose style, but it never satisfied me. I wanted to convey a story with depth and meaning and loose just didn’t work for me. When I switched styles it all came together for me and I could breathe life into my work. I rarely start a painting with drawn sketches. I start a painting with word sketches. I write words that say what I want to convey, then I choose my subject matter carefully to fit the words and message. It makes for some interesting “sketch” books. Is it technically challenging to be a realist? Indeed. It takes me at least three months to complete a full-size painting working 10 hours a day. But the difference is that now my paintings sing when I look at them and that is a joy.

AAS: Pencil Me In is just an amazing piece and really illustrates your skill. How much planning did that piece take?

Pencil Me In, 20” x 20”, watercolor

LSE: This is an excellent example of how I live the life I paint. I try to surround myself with cues for mindfulness. In this case, the planning was just deciding to share what I do all the time. In fact, someone asked for a photo of things I use in my studio and I removed these pencils (and a few other things) because I didn’t want to explain them. But my best friend noticed and tried to convince me it was okay to be a skosh more open. I’m on the fence there, but I said I would do a painting with them and see how it went. That is what started this series of five paintings, which includes the painting Daily. The hardest part of Pencil Me In was the portrayal of the stock market chart which is copyrighted material. I had to come up with different names and numbers that still at a glance had the visual look of what you see in print (but on a curve which is more interesting). That wasn’t fun, but it needed doing. I painted it with two light sources. That helped make two types of shadows, one dark and one light. So now that you have the backstory, I will explain. I work beside a northward facing picture window and next to me, at arms-length, sits a Mexican sugar mold that holds my supplies. My eye is drawn to my pencils that stand in the first mold. Save their unorthodox vestments they would hardly earn a second glance; but adorned as they are one might analyze their net worth as distinctive. Indeed, when questioned about them, I yield a smile. For to me they represent futures untold and that one’s share in it is truly a dividend.

Daily, 12” x 21”, transparent watercolor

AAS: Would you talk about the differences between watercolor and transparent watercolor techniques and what each brings to what you want to represent in your work?

LSE: Today transparent watercolor means you use no white paint. In other words, you must leave the white of the paper as the lightest part of your painting. So unlike acrylics or oils, you cannot paint a white or light highlight. You must plan your entire painting in advance to leave the white of the paper. The next layer would be the next lightest color(s), and so forth ending with the darkest darks. Choosing the brand, type, and color of paper will make a difference as to the way you choose to complete a painting. A watercolor can include white paint. Some watercolor paints are opaque, but can be thinned down to be transparent. If you add any white paint to your painting, even if it’s not used as a highlight it must be classified as a watercolor and not a transparent watercolor. For the most part I paint transparent watercolors, but there are some instances where a painting is better as a watercolor. And while we are at it, let me address paint in general. Watercolor paint is the same paint used in acrylics and oils and to paint your car. The binder is different. The watercolor brands we use today go through the same ASTM testing as oils and acrylics for lightfastness. A lightfast watercolor paint, and a lightfast oil paint exposed to the same elements and light will last the same amount of time. The paintings today are not Turner’s watercolor paint or even the paint from the 1970’s. They have the same standard as any oil or acrylic. I only use one source, excellent rated lightfast paint. These paintings will last as long as any oil and be beautiful and fresh. Don’t be afraid to purchase present day watercolors because you think they will fade. That should not be a concern. But do be careful when you purchase old watercolors, and have a professional framer take care of them. But in the same breath don’t put any painting in direct sunlight. Eventually they all will suffer from it. I also frame my paintings with UV plexiglass to protect them for the future.

AAS: Losing Traction is another wonderful piece with accentuated color and light. I am just in awe of the way you captured ageing wood and rust.

Losing Traction, 24” x 24”, transparent watercolor

LSE: Thank you! When I started painting watercolor I was told that everyone should paint a red painting. I’ve painted three. I love working with all the variations of red together. Each corner is different, and the sides read light to dark. The rusted portion at the bottom of this old caboose is, to me, beautiful. To portray rust in this way is so much fun, but admittedly a tedious process. So many layers! Beloved by children, it is quite unusual to see a working caboose these days since they are only used when there are dangerous chemicals on board. Best to see one in a painting or in a park.

AAS: 2020 Horizon is a charming piece. It is in the Permanent Collection and on display at the International Watercolor Museum in Italy. How did that come about?

Untitled (2020 Horizon), 8” x 8”, transparent watercolor

LSE: Actually, this piece has no official title. This was an international art performance suggested by [the Irish watercolorist] Aidan O’Reilly that was held by the International Watercolor Museum in Fabriano, Italy, during the second wave of the pandemic. Any artist could participate by posting a painting 20 x 20 cm on the museum platform that had to include a horizon. From the postings they chose 500 paintings to be aligned on their horizons in a giant virtual image posted on Facebook. A second selection, taken from the first, of 100 paintings would be a permanent physical exhibit in the Fabriano International Watercolor Museum as a testimony of the 2020 world watercolor community linked by art during the Covid pandemic. The IWM explained: “Covid has stolen from us the possibility to meet and physically cooperate. Art did not stop and we have used our brushes as a tool to stay strong and communicate to each other by online channels. Now with the new wave of virus, we feel again the need to propose the world watercolor community a challenge to be shared: a common project that together we can take care of, that can be done under the same sky by a far distance, through online tools, but must also be physically realized: let the horizon be our physical link.” My little painting was one of three chosen by United States watercolor artists for the permanent exhibit. I loved the premise, art linked only by a horizon. I was in the midst of painting a large piece and gave myself a week to paint three small paintings. I chose to post this painting and was delighted it was chosen for the permanent exhibit.

AAS: You belong to many watercolorist societies. In addition to the opportunities to show your work, what do these societies bring to your practice?

LSE: For me, gaining signature status in a particular watercolor society is a goal. Artwork can tend to be regional. There is nothing wrong with that, but I wanted to see if my work was competition worthy in any region. So, I chose to compete outside of the southern United States. I entered national and international venues for the same reason. The experience pushed me to become a better painter. I do think it is important to be a part of local art groups as well. These are artists you will see on a regular basis. Art can be a lonely activity with little feedback without access to a local community.