Interview with artist Paul Perkins

Paul Perkins is a North Little Rock artist who grew up in Oklahoma City. After high school he moved to Chicago to attend the School of The Art Institute of Chicago, where he earned a BFA degree. His art, motivated by his Native American heritage and beliefs around shared humanity, asks us to reconsider what we see as harmless and challenge preconceived notions about value, beauty, and consequence. More of Paul’s work can be found at his Instagram.

AAS: Paul, where were you born and raised?

PP: I was born and raised in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma. My partner and I moved to Little Rock based on her having a business opportunity here and for me, more studio space and to become more connected with my Native heritage.

AAS: Did you have any artist role models growing up?

PP: My mother was a Native American school counselor with Title IV in Oklahoma City, serving Native students and families for over 30 years. My mother was a half Muscogee Creek Native American making me and my brothers a fourth. She brought culture into the classroom through arts and crafts, making sure her students felt connected to their heritage. At my grade school, where there was no art teacher or art room, she became my first art teacher. Our dining table was my studio, and she taught me that creating Native American art was meaningful – that it mattered. Her encouragement empowered me to see art as a part of who I am.

AAS: Tell me about your time at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. From there you went to the Philadelphia Museum of Art?

PP: In Oklahoma City, I attended U.S. Grant High School. During my 9th grade year, in art class, the very last class of the day, a representative from School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC) came to give a presentation. They spoke about the school’s history, its place in the art world, the opportunities it offered, and the kind of creative community a student could step into if they went there. Sitting in that classroom, listening to the possibilities, something clicked. I decided right then that I wanted to go to Chicago, that I wanted to be part of that world, and from that moment forward it became my goal. Years later, when it came time to apply, I put everything I had into the process. I applied for a scholarship and was awarded one, which felt like a huge breakthrough. But the reality of leaving Oklahoma City and moving to Chicago was complicated. The dorms at SAIC were too expensive for my family, and it seemed like the dream might stop there. That’s when my high school art teacher stepped in to help. She had a close friend in Chicago, and after reaching out, arranged for me to stay with that family at a cost of $150 a month for a room. It wasn’t glamorous, but it made my dream possible. Even with that solution, going to SAIC wasn’t easy. I didn’t have much money, and living in Chicago was a constant struggle. Most of my time as a student, I lived in a dangerous neighborhood where the rent was affordable, the buildings were rough, and floors could be splattered with paint without anyone caring. But in a way, that kind of environment gave me freedom. It wasn’t safe, but it was a space where I could focus on making art, experiment, and grow without worrying too much about appearances.

The education I received at SAIC made that very difficult situation worth it. To study art on that level, in a place where the Art Institute’s museum was only steps away, meant I had daily access to one of the greatest collections of art in the world. The city itself was a classroom. Chicago’s architecture, its cultural institutions, its neighborhoods, its constant movement all fed into the experience. My professors were often unconventional and progressive, bringing knowledge not just from textbooks but from their own experiences in the contemporary art world. They were artists themselves, thinkers, critics, people who challenged student.

After spending most of my life in Chicago, I relocated to Nashville, Tennessee. During my three years there, I exhibited my work in Nashville, Indiana, Indianapolis, and Chicago. From Nashville, I moved to Philadelphia, where I joined the Philadelphia Museum of Art as part of the security staff. Just as I was beginning to immerse myself in the city’s art scene and galleries, the pandemic struck, everything was shut down. Throughout that period, I considered myself fortunate to remain on the museum’s skeleton crew. Walking the nearly empty galleries daily, I found myself surrounded by the collection in an unusually intimate way, able to study and absorb the works almost in solitude.

“For me, art is a constant state of becoming, where each work is both a continuation and a departure, opening another channel for expression.”

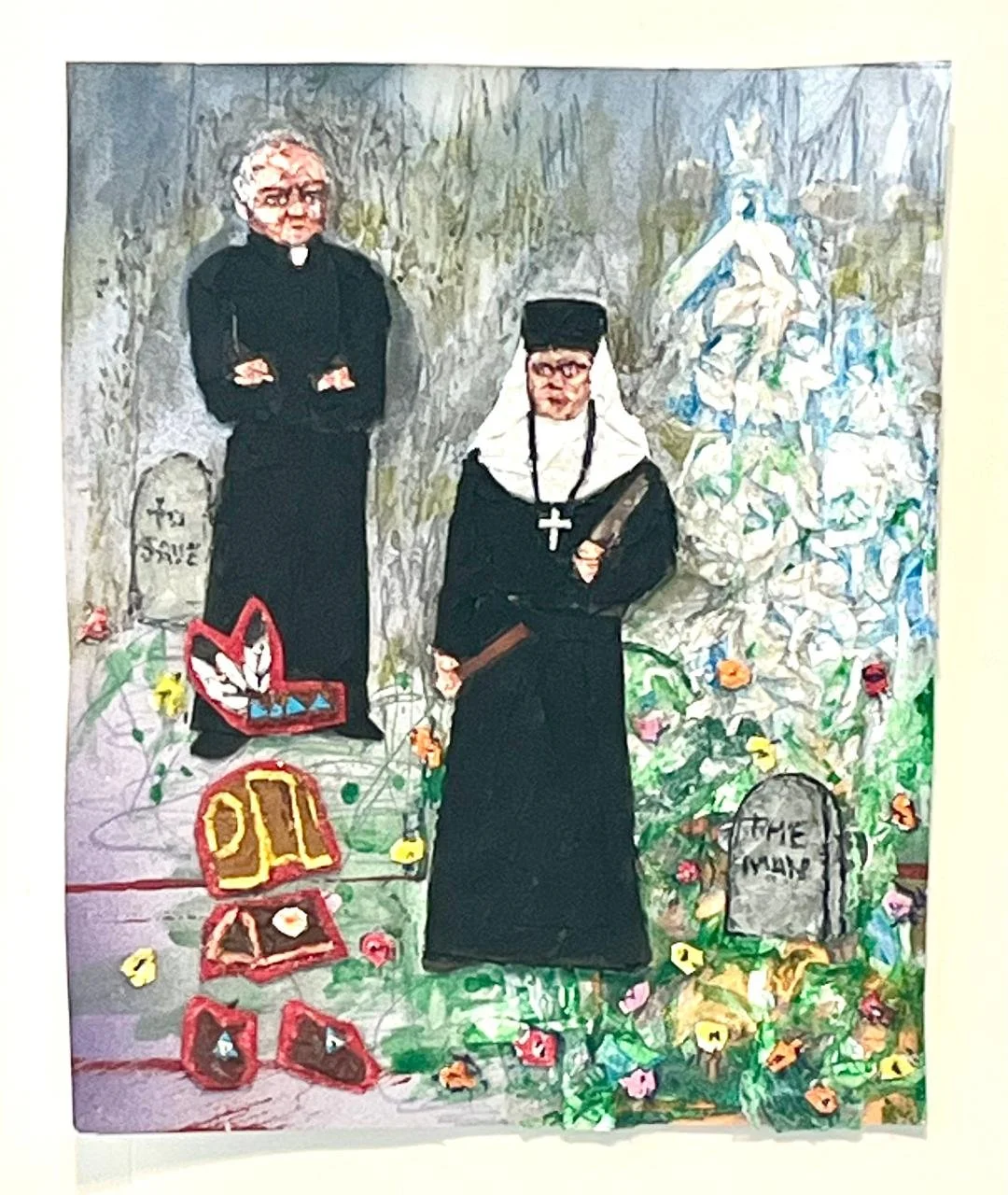

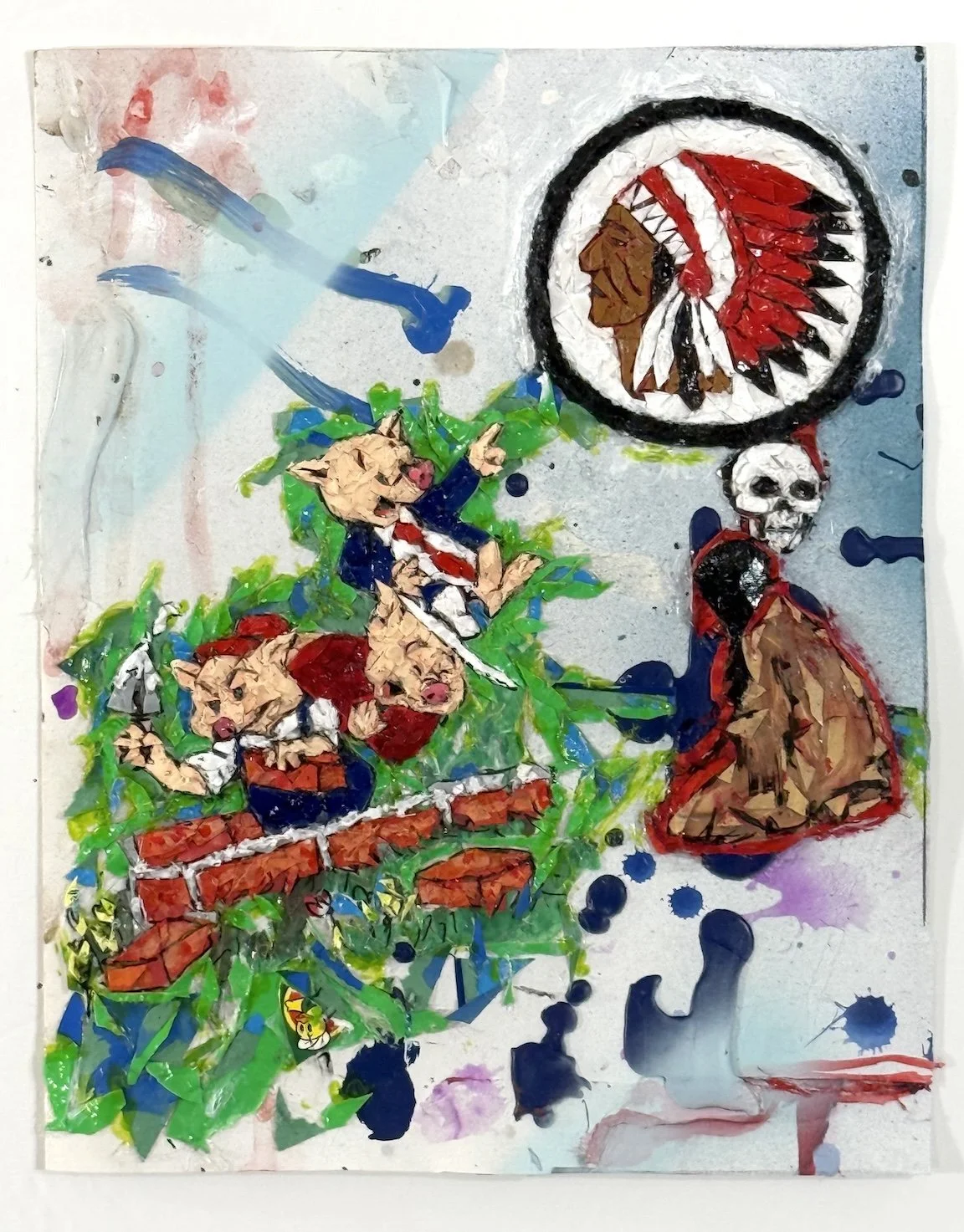

AAS: I think it is fascinating and admirable that you can work in so many different styles and media. For example, two that comment so differently on your heritage are Red Chief and From Front and Behind. Tell me about those pieces and what they represent to you.

PP: The Red Chief belongs to a series of oil pastel drawings that I consider ghostly visions—images that feel like spirits emerging from memory, or echoes of those who once existed. These works are both mysterious and intimate, as if glimpsed from the corner of the mind’s eye. In making them, I feel I am paying homage to ancestors, channeling something emotional and spiritual through shadowed forms that carry the weight of remembrance.

From Front and Behind is from another body of work shaped by Native American influences, but with a contrasting tone. These pieces are more cynical, analytical, even snarky—deliberately sharp in their humor. In spirit, they remind me of the Mel Brooks, western comedy movie, Blazing Saddles, where painful truths about America’s early history are confronted with biting, uncomfortable laughter. They have, for me, in creating them, violent laughter making sad tears. Through this series, I explore how humor can expose cultural wounds while keeping their weight ever-present. Behind the comedic stereotypical image there is the truth of it all – fear and pain.

These bodies of work shift between reverence and critique, between visions that honor what has passed, and satirical reflections that question how history has been told. As for my broader process, I approach artmaking as a vessel. I want to create as much as possible, in as many avenues as possible, without limiting myself to a single style or concept. The only true limitation, I feel, would be the absence of paper or any material with which to leave a mark. For me, art is a constant state of becoming, where each work is both a continuation and a departure, opening another channel for expression.

Red, Chief, 40” x 32”, oil pastel on paper

Front and Back, 12” x 8”, mixed media on paper

AAS: You’ve created some large sculpture pieces while at the SAIC that are commentaries on pop culture at the time. Was that for a student exhibition?

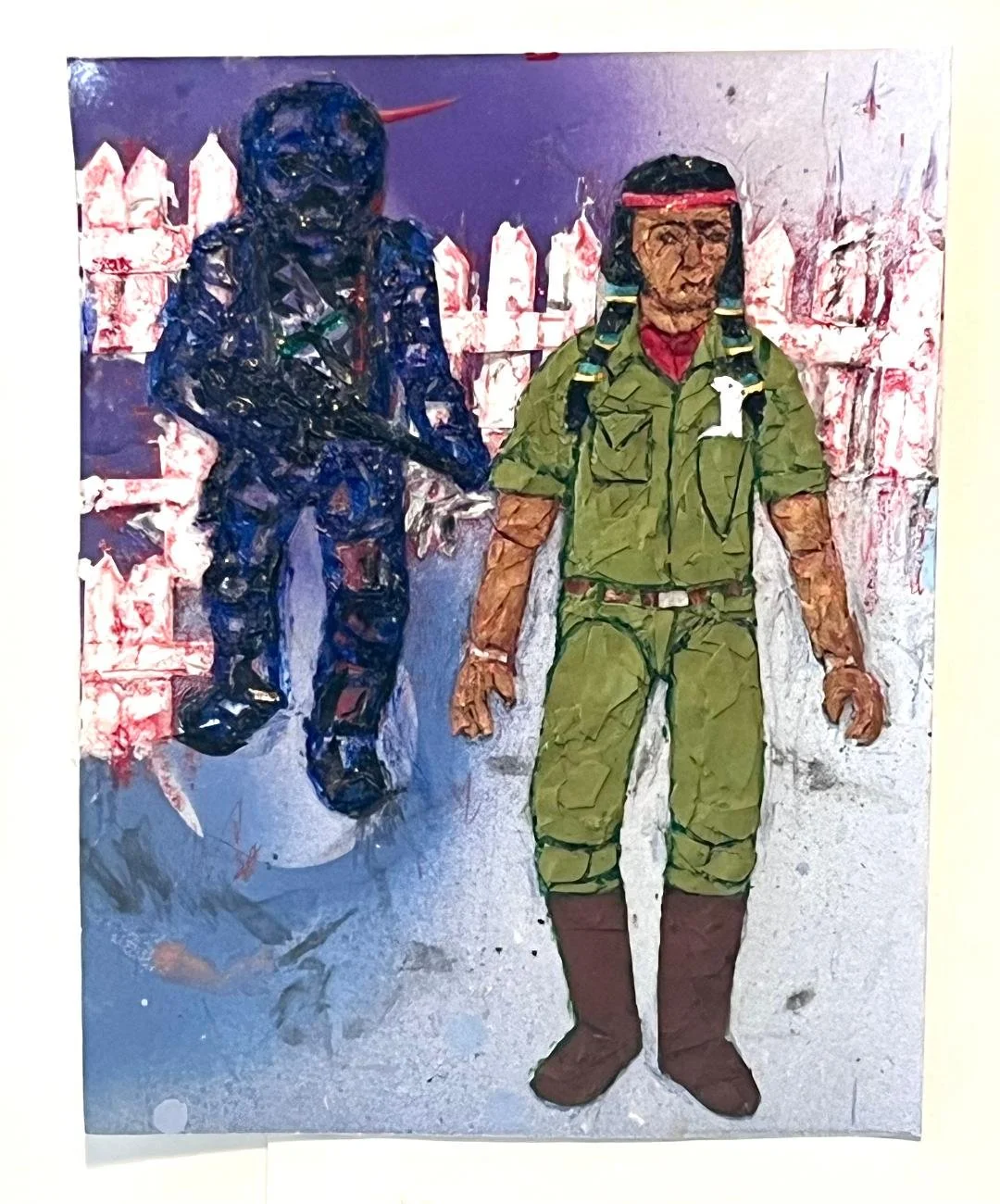

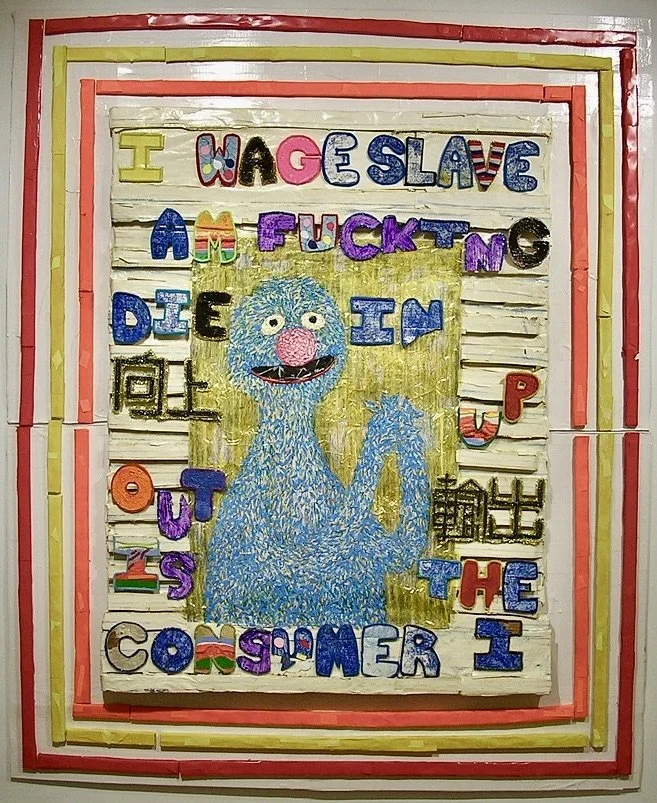

PP: I created some very large sculptures at SAIC but these large sculptures I created after graduating from SAIC. They belonged to two distinct bodies of work. Two of them, My Blue Monster and Captain America – Your on Your Own!, were featured in my solo exhibition in Chicago, titled, Dead Heat. These works embody my broader perspective as an artist: I see myself as a vessel, a reflector, a mirror that registers the thumbprints of culture and memory. The images and characters I work with often arrive as sudden flashes in my mind, and I recognize them as echoes of something larger—not created from nowhere but drawn from a collective stream. When I use figures from popular culture, I treat them as reflections of society, reference points through which I construct sculptural obstructions—physical dilemmas that take form as artworks. My process strips these cultural icons of their inherited powers and identities, peeling them down to a bare essence. What emerges is not their former image restored, but a new complexity—what I call my “thumbprints.” In this way, my sculptures become both mirrors and disruptions: familiar yet estranged, cultural fragments reimagined through the lens of my own making.

My Blue Monster, 5’ x 5’, wood, plastic, paint, glitter, felt, foam

Captain America – Your on Your Own, 5' x 3', wood, plastic, foam, paint, felt, glitter, cardboard

AAS: Your work often comments on social issues of the day. Two powerful pieces are Help Me Heat! from 2012 and Shooting Game from 2024. What I think is special about these pieces is the way you chose to depict the images and the construction and materials used enhance the impact. Tell me about them.

Help Me Heat!, 8’ x 6’, felt, paper, plastic, paint, craft sticks, tape, glue on cardboard

PP: Help Me Heat! was created in response to the tragic death of Trayvon Martin. It is a sad piece, born from reflection on a needless loss—the violent end of a young, innocent life. While making it, I found myself tracing Trayvon’s last hours, the ordinary and familiar rhythms of what he was doing that night. These were the same things many teenage boys, including myself at that age, would have done. Where I connected with Trayvon was in that shared experience of youth; where our paths diverged was in the brutal reality that he was profiled as a criminal because of the color of his skin and ultimately murdered. That difference haunted me, and I felt a strong need to create this work. The piece has always struck me as both a headline and a tombstone—something stark and declarative on its surface, but layered with dialogue, questions, and grief beneath. It is not just a work of mourning, but also a marker for the conversations and reckonings that must live on.

Shooting Game, 7’ x 5.5’, plastic, paint, craft sticks, tape on plastic board

With Shooting Game I wanted to show that toys are more than objects of play. They are reflections of who we are, what we value, and how we imagine ourselves. The toys we grew up with—the ones we fought with, played with, and collected—speak to the culture that produced them. Even the toys lining the shelves today carry meanings that extend beyond childhood. They reveal not only what entertains us, but also what shapes us. For years, much of my work has been drawn from toys I grew up with as an American child. I return to them because they are a mirror of our society. They construct identity, define roles, and rehearse narratives. In America, they often reveal something darker: the persistent presence of violence. Why have toy guns been so common for generations? What kind of games are taught when children play with them? What is acted out when someone is always the one who gets shot? In this sense, the American toy is inseparable from American society itself. Violent toys are not innocent—they are reflections of the culture that creates them. Through my work, I seek to strip away their surface of nostalgia and entertainment to expose the deeper questions they carry about identity, power, and violence.

“Through my work, I hope viewers reconsider the assumption that toys are simply harmless playthings. ”

AAS: What do you hope the viewers see and feel when they look at your work?

PP: Through my work, I hope viewers reconsider the assumption that toys are simply harmless playthings. By transforming familiar materials, I aim to make the work accessible yet thought-provoking—inviting reflection on the cultural values embedded in objects we often overlook. The main thing for me is to keep a viewer standing and looking at my work with questions and enough questions to make them come back look some more.The materials I use are extremely accessible—you can find them almost anywhere, especially in today’s craft store franchises where endless varieties and colors of supplies are available. There’s no need for gold leaf or rare, precious resources; instead, I turn to what is common, affordable, and familiar. Arts-and-crafts materials carry their own cultural associations. They are often considered “lo-fi,” reminiscent of childhood projects made with paper plates, construction paper, and glue. I’m fully aware of these properties and the way they can serve as reference points in my work. For me, accessibility and affordability are starting places, but the deeper interest lies in how these materials can be pushed beyond expectation. I use them to mimic or simulate the language of art history—the grandeur of epic oil painting, the permanence of stone sculpture—yet the subjects I choose often undercut that tradition: a toy gun play set, a Muppetesque figure. The tension between material and subject, high and low, fragility and permanence, becomes part of the dialogue of the work.

Paul’s studio with works in progress.

AAS: Your home studio is jam-packed but does that help feed your need to create?

PP: I have a constant need to create. From the moment I wake until I go to sleep, the impulse is always present. My mind races with images, narratives, and ideas—the deconstruction of this reality never stops. As a young person I was inspired; now, as an older artist, I feel haunted. I cannot turn it off. My studios are overflowing, packed with works in progress and pieces without destinations. The act of creating is both sustaining and stressful, because I keep making, regardless of whether the work has a place to go. I often stretch myself thin, beginning many things at once, then narrowing my focus onto a series or a single piece. No matter what, I always have something to return to, something to push forward. The studio is central to my life. It sees me more than my bedroom. Even if I spend only an hour there, doing nothing, its presence is essential. The studio is where I live as an artist—it is where the relentless need to create finds its place.

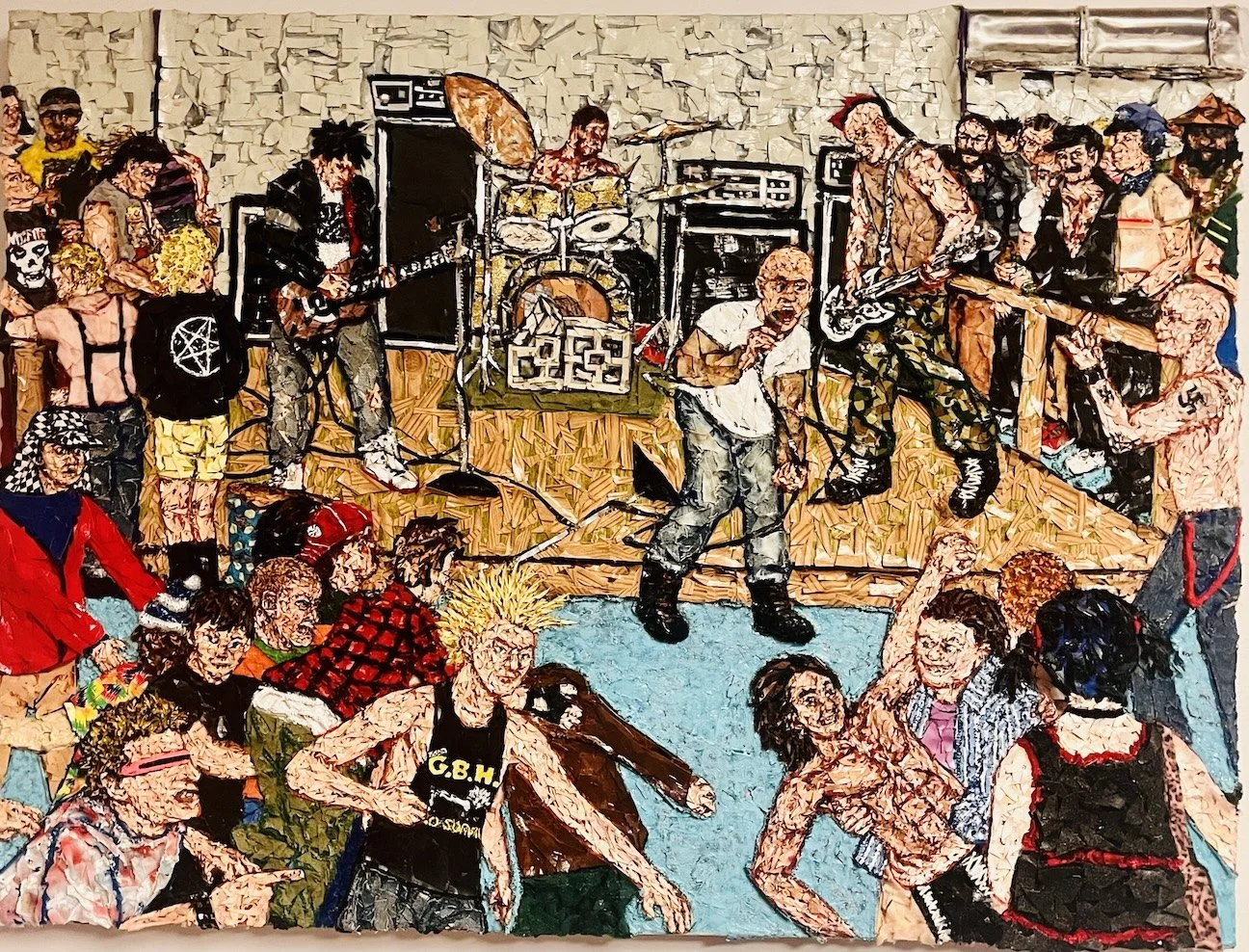

AAS: Under the Dome is an extraordinary work. Aside from being very large, it is filled with characters created in what I would call “2D relief”, which is a construction style you use frequently. Tell me about Under the Dome.

Under the Dome, 5.5’ x 7.5’, mixed media on wood

PP: Under the Dome is a work I have been developing on and off for more than ten years. Until I determine how I want it mounted, it remains unfinished, but it has long been a central piece in my practice. It is, in part, autobiographical—I see many self-portraits embedded within it. The first spark came from images of Hurricane Katrina, though over time the work has absorbed multiple layers of narrative. I resist telling viewers what I believe the piece is about, because for me it carries many possible stories. The overall event appears to be leading toward a violent altercation between several groups: the man in the red hat and his side, the Black man in the tank top and his side, the young Black boy before the police, and the police themselves. To me, the tension here feels familiar, drawn from the kinds of confrontations we witness daily in America. I believe most violent situations stem from misunderstandings, and that is embedded in this scene. Instead of depicting a leisure image—families on blankets in the park with wide sun hats—this piece depicts society through conflict, mistrust, and fracture.

Close up of Under the Dome

The origins of the work also draw from my interest in action figures. I wanted to take the language of the action figure and reimagine it within the realm of figurative sculpture and high art, using only accessible, everyday craft-store materials. In this way, the piece functions as a cycle for the viewer: you see the image and its narrative tension, then you begin to question how it was made, what it was made from, and how its materials shape your reading of it. Step back, repeat, and the dialogue continues. Ultimately, Under the Dome is built on both personal memory and public imagery. It is a composite of events I have seen unfolding in our society, brought into physical form to ask questions rather than provide answers. My hope is that the work holds viewers in that space of questioning—of what they are seeing, how they are seeing it, and why it feels so familiar.

AAS: Tell me about your involvement with the American Indian Center of Arkansas.

PP: Before moving from Philadelphia to Little Rock, I began researching Native organizations in the Little Rock area. Knowing I’d be closer to my home state of Oklahoma, I felt a strong desire to connect with my people. That search led me to the American Indian Center of Arkansas (AICA), where I became a participant in their program. Membership requires proof of tribal enrollment, and through it I was given the opportunity to contribute in meaningful ways.

My case worker—whom I call my Cherokee sister—invited me to do some work in their downtown Little Rock office. What began as a temporary job quickly grew into a deeper bond. As I spent time there, visions of old Native ancestors began to appear to me, as if emerging from the darkness. My sister helped me manifest these images, and in the process became a true friend. Over time, the office felt like a second home, and the people there like family. The work AICA does for Native communities throughout Arkansas is a blessing. For those who feel at the end of the line, the organization offers a renewed sense of hope. They have also given me artistic opportunities: publishing my artwork and a poem in their newsletter, featuring me as a Native artist on local television, and inviting me to make drawings live at an event. I continue to participate in their programs and will be showing my work in October for Indigenous Peoples’ Day.

I can’t say enough good things about AICA, but perhaps the best measure of what it means to me is the smile of pride I see on my mother’s face because of my affiliation with the program and with our people. Shout out to my Native sister—you know who you are.

AAS: Paul, what has the transition from the big city of Chicago and its art scene to central Arkansas been like for you?

PP: I have lived through many transitions, moving from one part of the country to another, each shift shaping who I am as an artist. Most of my life was spent in Chicago, where I received my education, faced a few curbside scares, and ultimately developed a sense of who I was and who I wanted to become. When my partner and I moved to Nashville, it marked what I think of as the widening of my perspective. From there, we moved again—to Philadelphia—trading the humid, slow southern drawl for the sharp, east coast Balboa, Yo! Now, in Little Rock, Arkansas, I find myself in the smallest city I’ve ever lived in. It is beautiful here, full of hills and waterfalls, though I have not yet settled into the local art scene.

I continue to work in my studio daily and am actively seeking gallery representation and opportunities to exhibit my work. I am also interested in opening my studio to the public, or at least to art enthusiasts, as a way of sharing my practice directly. Little Rock strikes me as a place well-suited for pop-up shows and experimental avenues of exhibition. I find myself drawn to the spirit of Fluxus—art as movement, art as action—and believe there is space here for something new to emerge. I am eager to connect more deeply with the Little Rock art scene, because I believe I have much to contribute.