Interview with artist Jean Schmitt

Jean Schmitt is a multimedia artist based in Fayetteville, Arkansas. She is also an assistant professor of art in the School of Art at the University Arkansas. Often through large installations, her drawings and sculptures explore natural history and ecology to invite viewers to consider their own participation with and contribution to living systems. She believes art should not be just something to look at, but something to encounter and learn from. More of Jean’s artwork can be found at her website jeanschmitt.net.

Who's in the Worm Bin,5’ x 10’, ebony pencil on Reeves BFK

AAS: Jean, where did you grow up?

JS: I grew up in Kalamazoo, Michigan. I left home at 16 to study music at Interlochen Arts Academy, where I took my first ecology class and discovered a love for ceramics. From there, I briefly studied natural history and birds at Prescott College in Arizona before attending Alfred University to study ceramics and sculpture. Since then, I have lived in Ecuador, Upstate New York, Boston, and Kansas City before moving to Fayetteville to teach at the University of Arkansas.

AAS: Was art something you were interested in even as a child?

JS: My interest in art was shaped by the kinds of curiosities and freedoms I had as a kid. I loved to color, and I loved being outside getting my hands dirty. My friends and I built elaborate cityscapes in the sandbox, made mud pies, and constructed forts out of sticks. Just as important as building was imagining ourselves inhabiting these worlds. Nature played a big role too—observing mosses and lichens, watching ants at work, paying attention to small systems unfolding close to the ground

I had two brothers and a sister, and I was the youngest, always wanting to tag along. My brother told me I could come fishing with him if I dug up the worms—so there were early worm influences too.

I also grew up playing the violin, and music taught me a great deal about passion, daily practice, beauty, and what a life in the arts could look like. One mentor, Paula Solkol-Eliott, introduced me to playing in a string quartet, where four people can learn to breathe, sense, and feel like one body. We traveled together, and I realized early on that I loved to travel for art.

Looking back, I can see how those experiences—building worlds with my hands, paying attention to nature, and learning collaboration through music—have shaped how I work as an artist today.

AAS: Drawing seems fundamental to your art practice. So, I want to ask you first about Worm Drawing and your use of a quite unusual medium, wheatgrass juice. Of course, I have to ask you what is it about worms that fascinate you?

JS: Drawing is fundamental to my practice. I’ve never thought of myself as a “good drawer,” and I still carry a lot of hangups around it. That makes drawing feel risky and challenging, which is why I keep returning to it—it’s a place where I’m constantly working against my own limitations. After more than thirty-five years of practice, that is beginning to feel easier to accept, because what’s on the other side of limitation is often a rich space of exploration.

I’m drawn to working at a large scale. Some of my drawings are very muscular, built by piling graphite onto paper so thickly that it breaks the grain and creates a deep shine. I make a few controlled decisions at the beginning, and then the work becomes about material and process. Floodwaters was a drawing about scale and time; it took a year to complete. When people talk about living in a time of overlapping crises, there’s both overwhelm and attraction in that idea. Making Floodwaters was beautiful and tragic, overwhelming and oddly addictive—I was often swallowed by the process itself.

Floodwaters, 4’ x 14.5’, graphite on paper

Worms Drawing, application of wheatgrass juice and worms to Reeves BFK

But when it comes to the worms, everything shifts. Drawing the worms in my studio bin at human scale—my scale—was about imagining the power of a collaborative community whose collective labor produces healthy soil. I was searching for a line language of worms, a kind of vermicular vernacular, and I had to ask myself whether it was presumptuous to think I could find it. The next drawing responds to that question. In Worms Drawing, the worms make the marks themselves, trailing wheatgrass juice across the paper. In its current form, that drawing took about seven months of working with the worms.

Worms Drawing, 4’ x 12’, wheatgrass juice on Reeves BFK

AAS: I am always fascinated by what drives multimedia artists. In your case, was it out of necessity to be able to explore the complex themes in your most recent works?

JS: It could be an inability to stay in my own lane. Or it could be that I’m incredibly curious—I want to know everything and do everything—so the profession I found for that was artist. Natural history, birds, and music continue to be passions in the work. I tend to think across media rather than in one, and I often partner with others to realize projects.

One example is a lithography series I’m currently developing with my son, Francisco Ormaza, who is a printmaker. Lithography is a highly technical process that involves drawing on stone and then carefully processing it to produce prints. Francisco is encouraging me to work with a much more immediate and fluid drawing style. It feels risky and unfamiliar, but he’s a good guide, and I sense a new series emerging through this collaboration.

Future Fossil, Worm Trails, 24” x 18”, laser etched Arkansas sandstone

But more to your question—let’s return to the worms. The anthropologist Arturo Escobar, channeling many relational cultures, says, “Things and beings are their relations; they do not exist prior to them.” I didn’t want to make work about this idea; I wanted to practice it. That meant I couldn’t just create artwork about worms—the worms needed to be active within the work. I do draw the studio worms, but other drawings involve them directly. They needed a space to inhabit the work, which led to the worm tureens and the choice of porcelain in this current version. A fossil-inspired piece laser-etches the worm trails from the drawing onto Arkansas sandstone. These materials mattered for the work to make sense—at least to me. This is how the multimedia approach grows organically, as ideas find form across different media.

AAS: Tell me about your installation Threshold Ecologies and your beautiful worm tureens.

Worm Tureen, Prototype 1, 38” x 27”, terra cotta, wheatgrass, worms, soil

JS: In the decorative arts, one of the loftiest members of any china set is the soup tureen. We had a beautiful one in my home growing up. I think we used it once. Mostly it lived on a shelf, and I loved that lidded porcelain form. Tureens sit in a strange place—familiar, ornamental, sometimes overlooked. Worms occupy a similar space: underground, out of sight, easy to dismiss. I’m drawn to this pairing.

The Worm Tureens bring these worlds into contact. Porcelain vessels become living environments—housing worms, soil, and wheatgrass, extending a decorative tabletop form into an ecological system. The tall stacking tureens push this further, into a more architectural scale: living sculptural systems sustained through use and care.

Made during my residency at Taoxichuan in Jingdezhen, the work draws on a long porcelain lineage while reimagining what a vessel might hold. I developed the forms and designs, which were thrown by master potters Hu Guo Tao and Zhang Ya Long. I worked with master painter Xie Li Qian to bring historical surface traditions into conversation with what happens inside: worms quietly making soil. One tureen features a Ming-style dragon—an echo of the earthworm’s old poetic name, the “earth dragon,” an unseen creature shaping the ground beneath us. Although the vessels were made in Jingdezhen, the work continues through ongoing care and conversation here in Arkansas.

I think of this work as part of what I call Threshold Ecologies—places where systems overlap and transformation is already underway. Compost is one of those thresholds. Soil is another. Even the tabletop can become a meeting point between domestic life and larger ecological processes.

The system is intentionally circular. Wheatgrass grown in worm compost is juiced and shared. The scraps return to the worms, completing the loop. Through the Worm Tureens, I’m interested in how art can create spaces for connection, shared care, and ecological imagination.

AAS: I want to ask you next about your installation Visible / Invisible. It features drawings and life-size white porcelain vultures, which are a wonderful visual contrast to the drawings. They must have been fun to create. What are you hoping the audience experiences while viewing the installation?

The Committee 2, Harbingers’ Table, 4' x 4' x 3.5', porcelain, stone, iron

JS: Vulture Committee is presented alongside Visible / Invisible, and the porcelain birds extend the project into the physical space of the gallery. Scale and grouping were essential for me—I wanted the vultures to feel present, almost as if they’re simply hanging out together in the room. Over time, I became interested in why vultures are so often culturally dismissed, and how that dismissal reflects whether we see ourselves as separate from or connected to the natural world.

The work began with a strange pairing of encounters. While “birding” at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, I came across a pair of life-sized Meissen porcelain vultures commissioned for Augustus II’s extravagant porcelain menagerie. Around the same time, I was watching vultures on the coast of Ecuador feeding on a large fish that had washed ashore. I recorded their movements and eventually chose to make life-sized porcelain versions—some standing watch, some crouched and feeding, some pulling at the carcass.

There are twenty birds in the series, each one distinct. Porcelain shifts slightly in the kiln—it wiggles—and that subtle movement gives each vulture its own character. Together, the drawings and sculptures invite viewers into a space where these much-maligned birds can be encountered with curiosity, respect, and care.

AAS: Tell me about large almost abstract drawings in Visible / Invisible.

Pepin, WI Vulture Flight Lines, 48” x 15“, graphite on paper

JS: I’ve been working with vultures for about fifteen years, in different ways. In the Visible / Invisible drawings, I focus on the spiral flight lines of vultures soaring on thermal air currents. The collaboration begins with the thermal itself—another natural form that’s largely invisible to us. As a vulture catches that rising air under its outstretched wings, it becomes like the tip of a pencil, drawing a line that holds the tension between air and wing. I record the birds and later extract the exact flight paths from the video footage.

The turning movement of these lines is sometimes called a revolution, and I think of these forms as holding the possibility of change. Anthropologist Arturo Escobar describes a “post-dualist ontological turn,” a shift toward understanding ourselves as connected to other beings rather than separate from them. The term is a bit unwieldy, but when I watch vultures circling—these repeated turns, these revolutions—I can’t help but feel they’re telling me something about connection and transformation. In that sense, vultures align closely with the processes of worms. As scavengers, they take what remains and convert it into new or continued energy. Lifted by thermals, they rise—sometimes as high as 32,000 feet. Despite this, vultures are often despised. I’ve never understood that. I see them as transformers, recyclers, and harbingers of change.

There is also a digital version of these flight lines. Climate scientist Zeke Hausfather recently quoted colleagues responding to current temperature data as “stunning, unnerving, mind-boggling, absolutely gobsmackingly bananas,” noting that scientists have run out of adjectives for what they are witnessing. As climate scientists strain to find language, I trace a vulture flight-path vector using their last words. When adjectives fail, it can feel like a passing of the baton—toward another way of sensing, marking, and witnessing change.

Vulture Drawing: Absolutely Gobsmackingly Bananas, digital drawing of vulture flight path

AAS: An advantage of being at a university is being able to gain inspiration not only from other artists, but also from those in science and technology. Tell me about your interest in mathematics and illustrating mathematics.

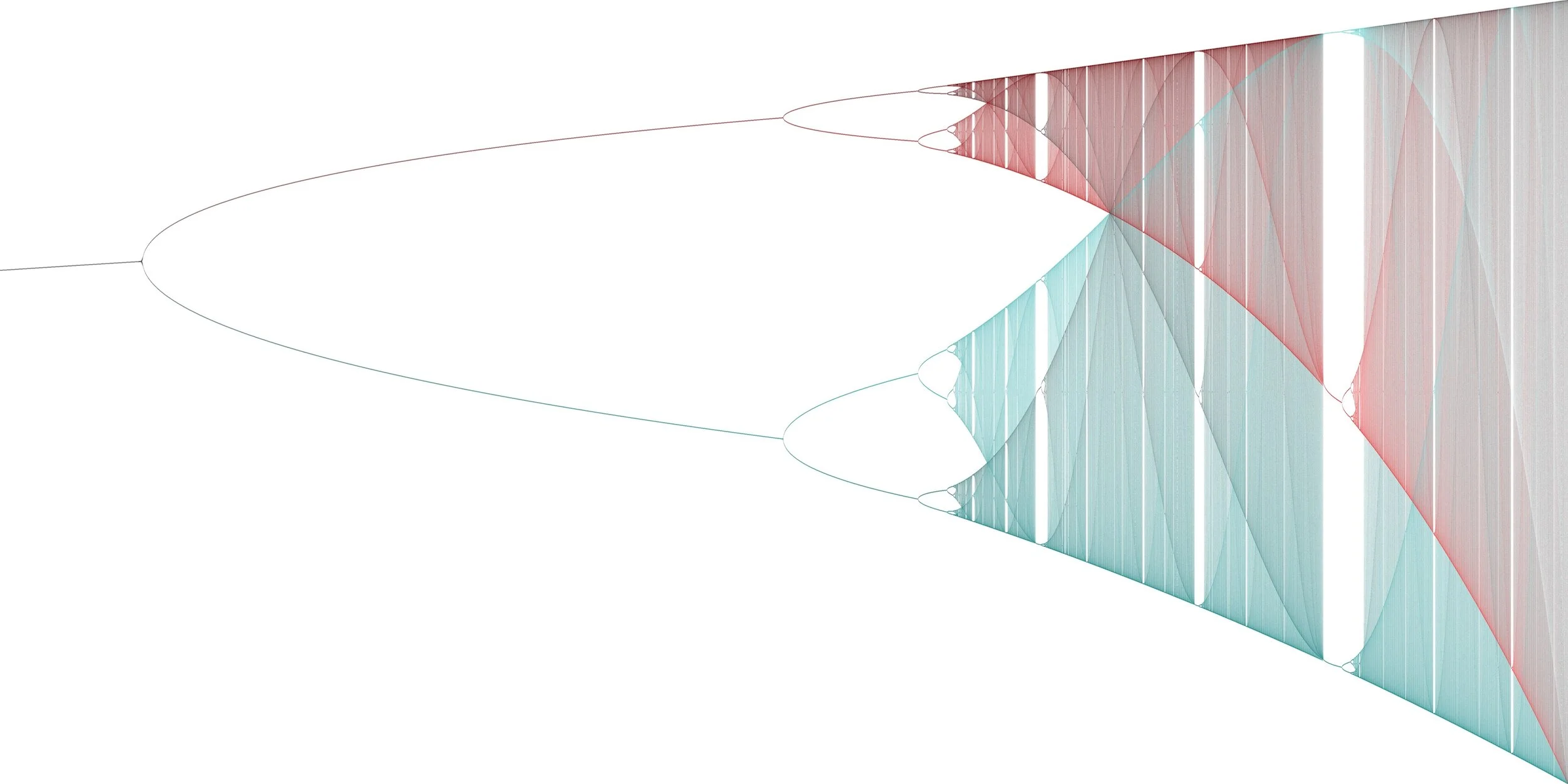

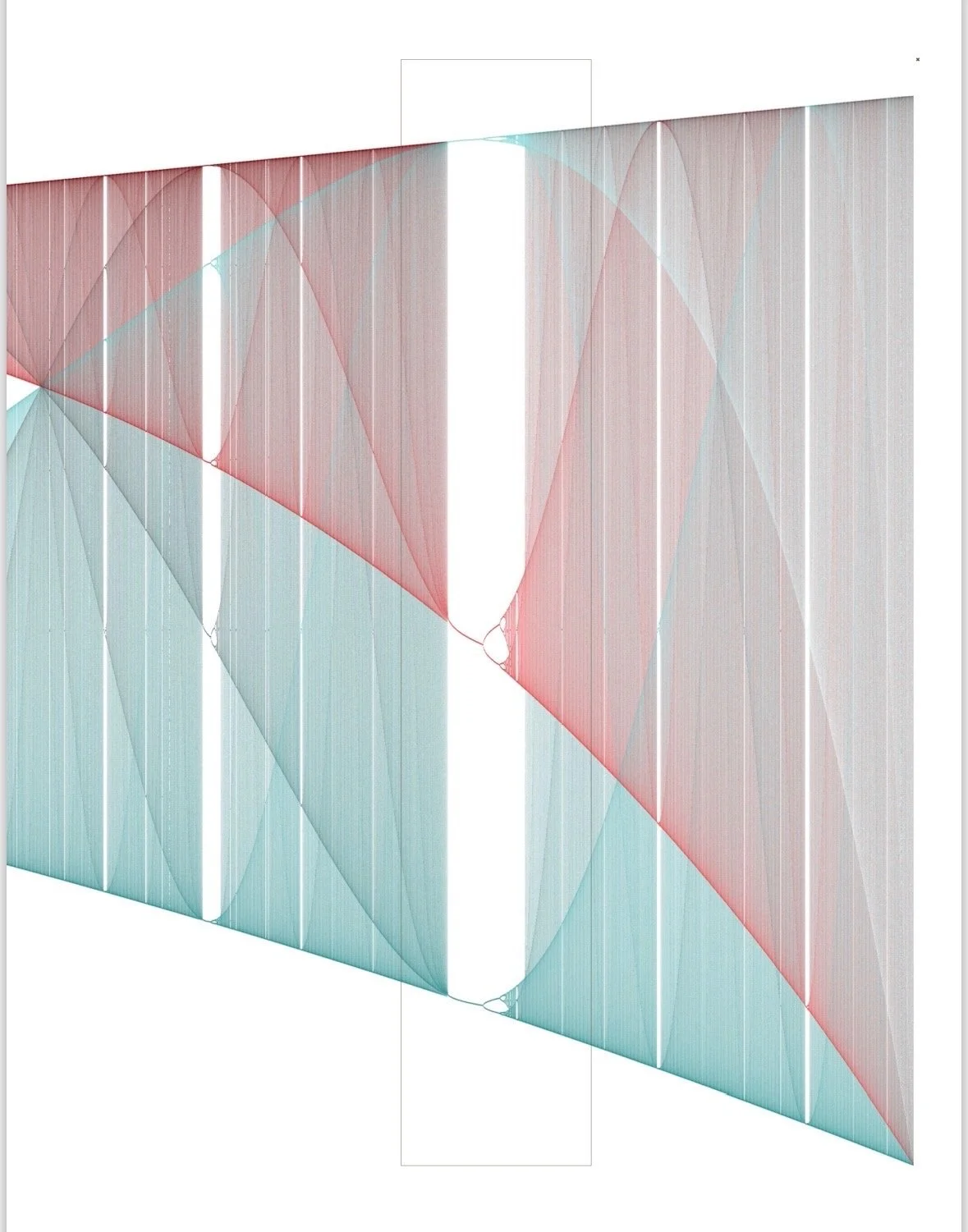

JS: I was approached by my colleagues Edmund Harriss, a mathematician and artist, and Vincent Edwards, a technologist and artist, about a collaborative project for an exhibition at the Poincaré Museum in Paris. The call invited works in which the illustration of mathematical concepts is understood as a form of research—borrowing from studio investigations to show how ideas develop and how knowledge can emerge through tools, materials, technologies, and form.

We wanted to explore a simple question: how does order give way to chaos? We borrowed the bifurcation diagram from chaos theory, which shows how a system governed by simple, rules shifts from stable order toward overlapping complexities and chaos as small changes in conditions amplify and become unpredictable behavior. In the work, equations are translated into machine code that controls a 3D clay printer, generating forms and surfaces that show increasing instability as parameters shift. We also collaborated with Mathew Conroy at the University of Washington to convert the diagram into sound.

For mathematical illustration to function as research, it needs to remain faithful to the mathematics. For it to function as art, it also needs to engage material, form, and the tools required to produce it. Finding that balance—staying true to the idea while allowing it to take material shape—is what makes the process compelling. The resulting work, Misshapen Chaos: Of Well-Seeming Forms, will be on view at the Poincaré Museum in Paris this April.

AAS: Congratulations on receiving a 2025 Arkansas Art Council's Individual Artist Fellowship Grant. What will that support?

JS: Thank you! This is a great honor. Especially because of the way it recognizes an underground an unseen creature that is pretty humble. This multisensory series has many next steps and stages. I would like to develop the next stage of the stacking tureens and the table-top tureens. The hope is to make the table-top tureens into a functional set that might be attractive to have in homes, a sort of artful vermicomposting system, that includes wheatgrass. I brought back molds from Jingdezhen but need to work on the production part. I also need to design wheatgrass juice cups to complete the set. There’s never a lack of things to do next!

AAS: Tell me about the art program at the University of Arkansas and what do you teach there?

JS: The School of Art at the University of Arkansas is a really dynamic place right now. We have students who are ambitious, curious, and engaged with the world around them, and the program supports a wide range of practices—from studio art and design to art education.

Some of the most exciting growth in the School of Art has been made possible through an unprecedented gift from the Walton Family Foundation. It’s creating access and opportunity for students from all over the state to pursue a dream in the arts—often in ways that simply wouldn’t have been possible a generation ago. You can feel that momentum in the program: students are taking their work seriously, and the school is growing into what it can become.

I teach in Foundations, which is the first year of study for students entering the School of Art. It’s an introduction across media, but more than that, it’s about learning how to begin—how to embrace uncertainty, build creative habits, and develop confidence through making. Our students have been through a lot, and you can see that in their work: some are drawn toward design as a way to address community needs, others toward storytelling, care, humor, or big ecological and social questions.

For most artists, the answers don’t arrive fully formed. They emerge through the daily practice of working—through questions, experiments, and attention. In the School of Art, we try to give students the tools, the community, and the support to let that process unfold, and to discover where their work can lead.