Interview with artist Joli Livaudais

Joli Livaudais moved to Little Rock, Arkansas in 2014 after earning an MFA from Louisiana Tech University. Currently, she is an associate professor of art and teaches photography at the University of Arkansas Little Rock, Department of Art and Design. She is also the graduate program director. In her art, photographs are more than memories. They are transformed and reborn to celebrate the past in unique ways, which have earned her national attention. Joli’s work can be found at her website joli-livaudais.com.

AAS: Joli, where are you from originally and what path led you to Little Rock and UALR?

JL: My father was an engineer who worked on construction of nuclear power plants, so the end result was that we moved every several years similar to a military family. My parents’ roots were in Texas and Louisiana, but I was born in Chicago and lived in upstate New York, New Jersey, Tennessee, Louisiana and Texas before setting out on my own. I joined the Army after high school with the intent of paying for my college education, never dreaming that we would actually go to war --- it was 1987. I did go to Saudi Arabia and Iraq for Operation Desert Storm, which was an eye opener. I count myself lucky as that first war was much less traumatic for the soldiers than some of the conflicts that followed after I completed my four-year commitment. After the military, I started working on getting my degree. Although I had played with the idea of being an artist or a writer in high school, I wasn’t confident enough in my abilities to be too serious about it. I settled on psychology and earned an undergraduate degree in psychology and a minor in art at the University of Texas at Arlington. This is where I first discovered photography. I will never forget the moment I realized I truly loved photography. It was all traditional darkroom then, a few years before digital took over. I liked to go into the darkrooms to work at night, when I could have the space to myself and play music while I worked. I went into the darkrooms at 10:00 one night, and I knew I had been working quite some time, but when I checked my watch I realized I was missing my 8:00 am Spanish class. I had experienced a “flow moment” and completely lost track of time! I was really torn about what to do. It was too late in my degree to make a switch, and I did—and still do—love psychology. In fact, after my MS I decided to begin work on my PhD in psychology. But I was in the program for less than a year before I knew in my heart I had made a mistake.

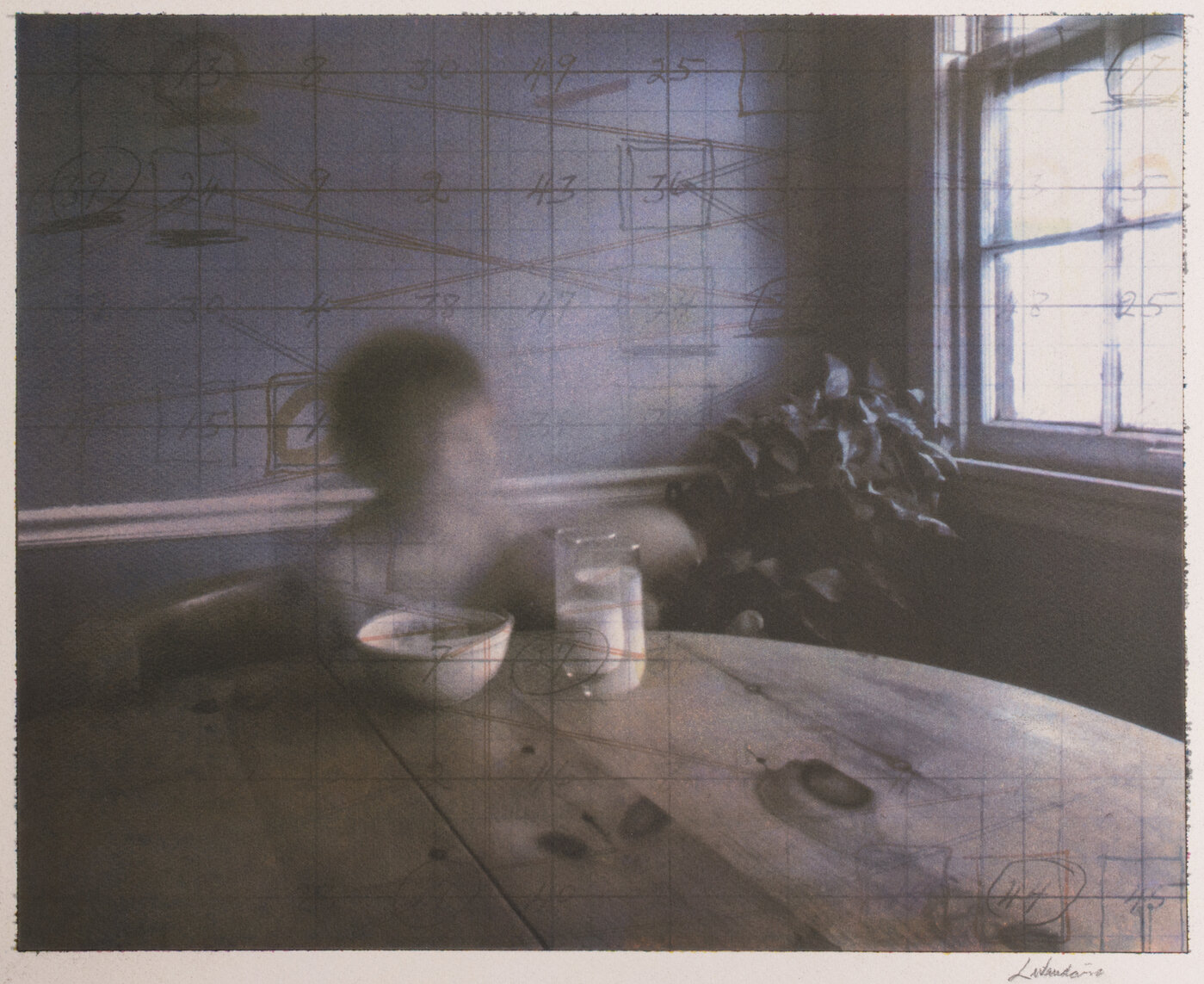

Uneasy Domesticity, photographic print, 17” x 14”

All my life I had been making art while doing other things, but once I was in graduate school there was no time for anything but my studies. I was absolutely miserable. I had no idea how much art had mattered to me until it was taken away. I decided to finish my MS just so I could have the credential in case I needed it in the future, but after that I started working as a photographer’s assistant for the commercial photographers working in Dallas. It was a tremendous education on the technical skills needed for photography. I did that for a few years, and then began taking small shooting jobs myself and acting as first assistant and second shooter for established photographers. That’s when I met my husband, Jason Grisham, on a photo shoot. Jason was the art director for an agency that was handling the Skeeter Bass Boat catalog, and I was assisting the photographer for the project. After the 6-week long project wrapped, Jason and I began seeing each other seriously and I moved to Louisiana and we married. We set up a commercial photography studio and gallery for me there, and I ran the studio while attending Louisiana Tech University to earn my MFA. I had always known it was really fine art I wanted to do, and the opportunity to teach seemed like a perfect fit to me, so going back to school was something I wanted terribly! And it was well worth it. I was hired as an assistant professor of photography for UA Little Rock in 2014.

“Life is about a million small moments strung together, and the grind of doing the work, and my process replicates a small part of that.”

AAS: It is interesting that you have a masters degree in experimental psychology. Do you think your training in psychology has influenced your artistic expression through photography?

JL: I think that my studies in psychology profoundly changed me and how I see the world. I also think that psychology and art are actually tightly linked. Both are inquiries into the human condition — the difference is that in psychology, you make the assumption that answers can be found and set about doing just that, and in art, it’s really all about the questions. My psychology degree was in experimental psychology, not counseling, so I think the way it changed me most was that it taught me to be a scientist. As a young woman, I don’t think anyone ever accused me of being logical or methodical, but they are definitely qualities I have now, and I attribute that to what I learned earning my MS. I was always a hopeless idealist, so I think I needed that to become a balanced person and a better artist.

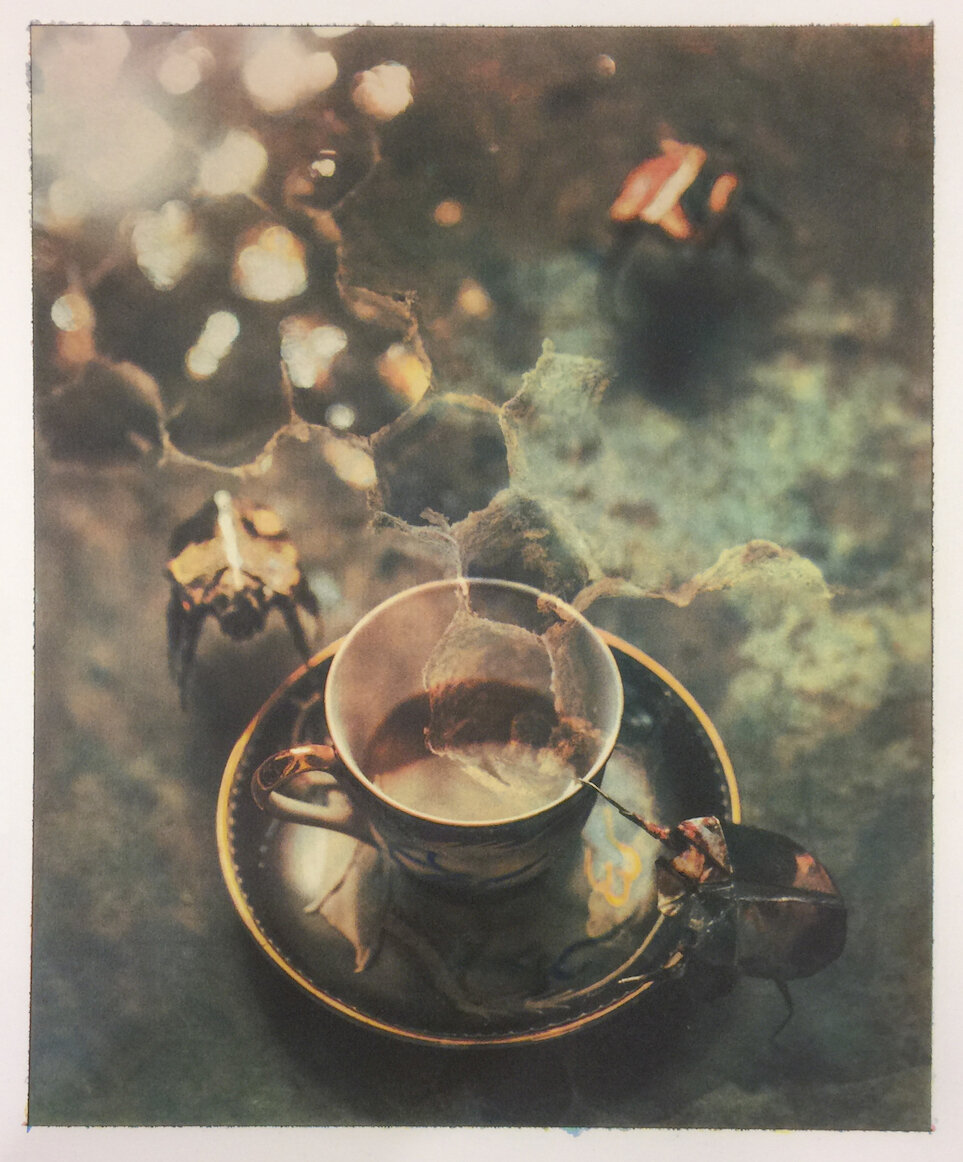

Ash Hands, photographic print, 17” x 14”

AAS: Your photographs are often deeply personal, and you’ve written about your recent series, And Then I Will See, created using a pinhole camera and the historical process of gum bichromate printing. Would you comment on this series and what the images mean to you?

JL: In 1978, John Szarkowski published an essay titled “Mirrors and Windows: American Photography Since 1960”. In this essay, he states that all photographs are either windows into the world or mirrors into the mind of the artist. My work is definitely a mirror. I use it to ask questions and think on my life and the forces that shape me, but I think there are many who share similar experiences and that my work is made in such a way that others can find themselves in it.

And Then I Will See is a very personal series, and it requires a bit of story-telling to explain. My mother had cancer, and it financially devastated my parents. When she died, my father fixated on winning the lottery as a solution to the crisis. He believed that there are patterns in the universe, and that by studying nature they can be discerned. Things we believe to be random can be predicted, if the variables are understood. He spent the next several years working on discovering the pattern. Every day he took thousands of random samples of numbers and placed them into color-coded grids that only made sense to him. I have many conflicting emotions about my father, because he and I were not close. He was a difficult man to love. But when he died, and I sat with the boxes of pages of gridded numbers, I recognized much of myself in the pages...the study of nature in search of something deeper, the same desire for meaning and order, the same tendency to obsess. Although I would deny it, I am my father’s daughter, and that means both good and bad things. In the photographs of this series, I study nature, beauty, and the minutia of my own life in the context of my father’s data, with all the emotion and ambiguous connections that such a study implies. The images, captured on black and white film with a lensless pinhole camera and often layered with photographs of my father’s numbers, are hand colored and printed in the layered, historical process of gum bichromate. This highly involved process yields images that are softly focused and reminiscent of a constructed memory.

AAS: I want to ask you about the current exhibition you are in, Arkansas Women to Watch: Paper Routes, at the Brad Cushman at UALR. I have not seen it yet in person, but what I have seen during zoom events I attended on the exhibition, suggest it is quite spectacular. Would you first talk about how that exhibition came about?

JL: The National Museum of Women in the Arts, located in Washington DC, has a biannual themed exhibition called Women to Watch. In this exhibition, they showcase women from all over the world who are making art but might be missed by the art community because they are not in the big art hubs like New York or London. I had the huge honor of being chosen to participate in the Women to Watch 2020: Paper Routes exhibition, which was all about artists who use paper as their medium. The Arkansas Committee for the National Museum of Women in the Arts put forward four fantastic artists for the DC show, chosen by curator Allison Glenn, Associate Curator of Contemporary Art at Crystal Bridges. The NMWA chose my origami beetle installation, All That I Love, to be part of the DC show, which ended in January. For 2021, I have the honor of touring Arkansas with the other three amazingly talented women artists curated by Allison Glenn. I am excited about this tour; for the DC show, I was not able to personally install my artwork because of the pandemic, but I will be able to install the work for these shows, with safety and pandemic protocols closely followed.

All That I Love (detail), origami made from photographs

AAS: I am just fascinated by your use of personal photographs turned into origami scarab beetles for All That I Love. For me, it’s the notion that the memories they carry can shape our future. It is brilliantly executed and vivid for sure. Would you talk about that installation and the development of its concept?

JL: I wanted to make work about memory, life, and loss. All That I Love is a layered work, in that I think viewers are free to take as much from it as they want to. For many, it is simply a whimsical and colorful wall of “bugs” (I never call them bugs, they are always beetles to me) and I am perfectly fine with that reading of the work. There is definitely an aspect of whimsy and humor in the piece, and the beetles are often vibrant and truly beautiful. I am, at heart, still an idealist and an optimist about life, and that outlook shows in how I approach the installation, with beetles dangerously close to electric sockets, teetering off corners and vents, and hovering near light switches so the unwary grab them by accident when turning on the gallery lights at the beginning of the day. But the scarab beetle is symbolic for death and rebirth, and the art of origami is a transformational one, where nothing is added or taken away but in creating the work the materials are profoundly changed. For me, the piece is about treasuring and letting go all of the memories and moments that make up a life, and understanding that in the end, the atoms that make us up will be given back to the universe and turned into something new. The use of the origami process to create this transformation, into a creature symbolic for death and rebirth, seemed the perfect thing to communicate those thoughts.

The amount of time that the work takes is also meaningful conceptually. There are 1434 beetles in the exhibition. This number doesn’t mean anything in particular—I just made as many as I could—but each beetle takes about an hour and half to make, so that’s over 2000 hours of work over the last two years. Life is about a million small moments strung together, and the grind of doing the work, and my process replicates a small part of that.

AAS: I have always been fascinated by origami and the skill and creativity it requires. When were you first introduced to origami?

JL: I had not done any work with origami until I started work on All That I Love. At first, I naively did not expect it to be difficult, but I was quickly schooled on that account. It is an amazing art form, and designers of some of these models are brilliant beyond my understanding. Now, origami, folding, squares and grids often appear in my work in different guises. To me these elements have come to represent logical thinking, and the mental constructs we create when we contemplate reality. After all, an origami beetle doesn’t really look like an actual beetle. This is not accidental; I could have used other means to create beetles that were more realistic. My understanding of the world is imperfect and limited, and the origami forms communicate something of that.

AAS: The exhibition also features Imperata Grassland – origami grass created from memories captured in photographs. To me this one is all about the often hidden interconnectivity we share with so many who have crossed our lives. How did this concept develop?

Grassland: Root System, origami made from photographs and metal, 53” wide, 19” deep

JL: My most recent piece, Grassland: Root System, is definitely about interconnectivity between people and the depth and complexity of things below the surface to which we are often oblivious. Imperata Grassland is really about life in the face of adversity. During one bad patch in my life, where I was dealing with significant situational depression, I began the practice of counting the beautiful things I could see. It was a way to keep me in the moment, and it gave me something to cling to when I felt like I was drowning. Later, I started photographing these things, and even when my situation improved. I continued the practice because it helps me to remember the good things I have in my life. Most of the images used in my installations come from this practice. Wild grass is so hardy, and quick to thrive, and humble, that it became a powerful symbol to me for survival. This piece has 947 pieces in it, and took over 700 hours to make not including the time spent failing at it and making prototypes (which was considerable—a great many things I try don’t work right away!) so it’s also a labor of love.

AAS: Your installations really play off light and especially shadow. I love your use of 2-D objects (photographs) to create complex 3-D experiences. Do you always have control of the shadows your shapes produce in a given installation and how important is that to what you want as the ultimate experience of the viewer?

Imperata Grassland, (installation), origami made from photographs

JL: Photographs are made from the record of light reflecting off of surfaces, and I am always aware that as a photographer light is my true medium. This awareness extends into the light within my photographs, and the light on pieces in the space when they are exhibited. It is very important to me that light be controlled, that the shadows the pieces cast be an active part of the viewer’s experience, and the few shows I have participated in where that hasn’t been prioritized have always been deeply disappointing to me.

The Mother, Exhumed, epoxy resin, pigment ink, kozo, 42” x 16” x 8”

AAS: And then there is The Mother, Exhumed and The Womb – two very powerful works. How are these constructed?

JL: The Mother, Exhumed and The Womb were made around the same time period and they definitely speak to each other. For both of these works, I created a mold and filled it with epoxy resin to create the foundation of the sculpture. I also wanted drips on these pieces, so after making the basic form I suspended them and coated them every few hours with resin to create the long hanging drips. This process often took days, and many coatings, in a sped-up version of how cave stalactites form. I feel this process creates ideas about honey and textures, both slick and sticky, and introduce ideas about time and process. My themes of life, death, and patterns emerge in these pieces, but I was also contemplating motherhood, female sexuality and service to others in these works, for which the bee seemed the perfect symbol.

AAS: You participate in a lot of exhibitions, both group and solo exhibitions, in Arkansas, Texas, New York and New Orleans. With as much teaching as you do, how do you find time to create your own art and prepare for shows?

JL: My chosen artmaking processes are all very time consuming, which is, to be honest, not the smartest way to approach it when you are a full-time educator. Teaching is a demanding job, and I love it and care about it, so I spend a lot of time on my students. Art has become the thing I do for fun, the thing I do when I am sitting with my family to keep my hands busy, something I do when I should probably be at the gym. I have a theory, that the world is such that we never have time to do all the things that we would like to do or that we feel we should do, so our true character is revealed in what we choose to prioritize. For getting the work out into the world, I apply to Calls for Art, and submit proposals for exhibitions to venues that I think are a good fit for my work. Websites like callforentry.org and entrythingy.com are great resources for artists looking to find exhibition opportunities.

AAS: As graduate program director, what advice do you have for MFA students who are thinking about academics.

JL: Art is a competitive field, whether you are trying to find a teaching job, run a gallery, or make a living in a chosen art field as a working artist, but opportunities are out there for people who are willing to work hard and be persistent. I think a lot about “grit” – the ability to keep going even when faced with significant obstacles. I firmly believe that success is tied more to grit than to talent, intelligence, or connections, and that this is true in every field, not just art. My advice to MFA students, or artists of any type, is just…don’t give up if it’s really important to you. There will be setbacks and rejections, but that’s true no matter what you do, so do something you love.