Interview with artist DebiLynn Fendley

DebiLynn Fendley is a native Arkansan living and working in Arkadelphia. She earned Master of Science Education degrees in both Art and English from Henderson State University and a Master of Fine Arts from Goddard College. DebiLynn has taught at both grade school and college levels; teaching and giving back is a big part of what drives her to create. Her works are exhibited extensively around Arkansas and the US and are widely collected. More of her work can be found at debilynnfendleystudios.com.

AAS: DebiLynn, are you originally from Arkansas?

DLF: Born and raised here. I’ve often wished I’d have been born in some place with more artistic opportunities, but then I have to wonder if I’d have the same ideas and concepts. Probably not. Early on I drew from my imagination to illustrate stories I wrote, and there was never any argument in my mind that I was an artist and a writer. I also traced a lot, mostly from animal picture books and illustrated stories I liked, before I figured out that I could actually draw what I was looking at. Later, I drew from comic books until I discovered the art history section in the reference books in the school library in the eighth grade. After I fell in love with Rembrandt and Dürer, there was no looking back. The comic books went bye-bye and I took a serious interest in learning how to make art. That and reading and writing were everything to me. My father encouraged me, and I have no doubt if he could have afforded it and if there had been training nearby, he would have sent me. I finished degrees in art and English at Henderson State, but I also traveled to study with artists I was impressed with, photographers like Steve Anchell, who to this day remains an influence and a friend, and numerous printmaking studios. Finally, I finished an MFA in Interdisciplinary Art from Goddard College in Vermont, which I’m now proud to say ranks amongst the top three or four private universities in the US.

AAS: You’ve trained in printmaking, painting, photography and film – and are working in all four and maybe more. Is it your need for artistic expression in any given moment that takes you to one medium over another?

Back, copperplate photogravure, 8” x 8”

DLF: It depends on the subject matter I’m handling and how I best feel the subject would be represented. Right now, I’m aching to do more photography, but the loss of my usual place to photograph has hampered that. In the last two years, I’ve seen my reach in photography really grow in terms of publication and exhibitions, and that’s been a surprise to me because I started using photography as a reference for my painting, and now it’s become an art form in its own right. My piece Back is a photogravure, an old process in photography and printmaking, being one of the earliest methods to print photographs. It involves an arduous process with cancer-causing materials, so full suit up and a very clean environment is required. I only know of two or three places in the US that can teach and produce photogravures; one is Crown Point Press in San Francisco, which is where I went to produce my photogravures. It's a costly process, and I'm always excited to meet someone who also has done photogravure.

I’ll have some decisions in the future as to how that will change my painting, and this may be the year that it happens. My printmaking is in flux as I have moved and need to build a new printmaking studio, and I miss it terribly. And are there plans for more film work? Certainly, but it will be in the future when I have more license to travel and more funding for the work. Filmmaking is all about funding. If you don’t have it, forget it. It’s not happening.

AAS: Even though you work in a variety of media, I see a common thread – almost a social commentary.

DLF: Absolutely. I found during my tenure at Goddard that I had a heart for contextualizing my work and a need for knowing what was influencing the art I made. I’d always had a need to inform my work through study and contemplation, and as I moved my study from books to primary source investigation, I discovered people who maybe didn’t like to answer questions for others would answer them for me. I’m told it’s because I’m transparent and they can see my motives come from a place of caring rather than curiosity. I have a love for underdogs and those who don’t directly fit into society because I feel myself in that same place. I probably will always be in that same place because I don’t fit in any one niche’. I’m a Bible believing gal that grace chased, and I believe in extending that grace to others in ways other people don’t seem to think about.

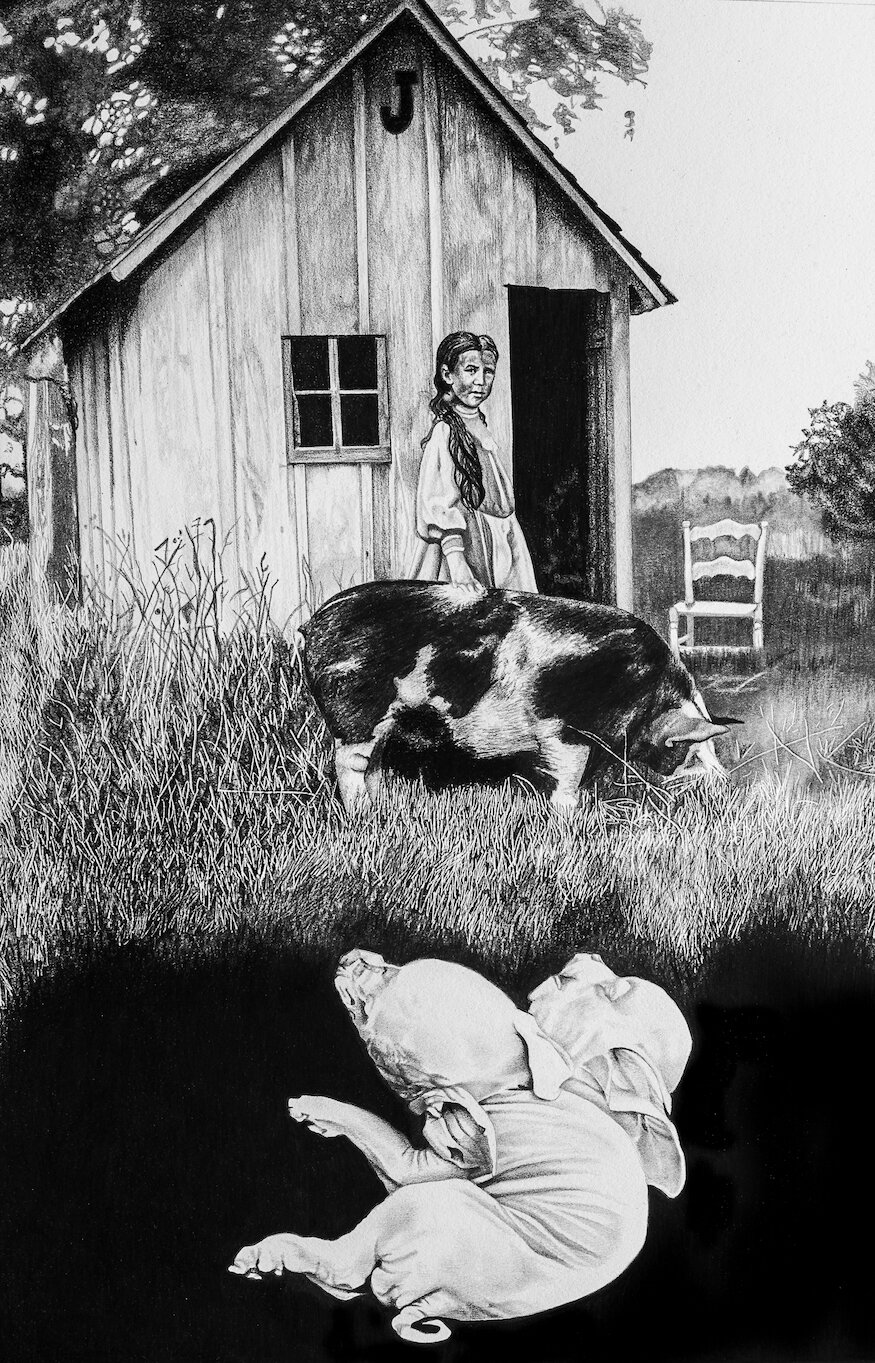

The Drunkenness of Noah, graphite on paper, 30” x 22”

AAS: Some of your works have tension created by light and shadow and angle and perspective. Would you comment on that?

DLF: I’m a big fan of chiaroscuro in art. I quite often work with only one light source because it gives me deep shadows and hidden spaces, which in turn often says much about the subject matter or idea I’m trying to convey. I’ve been heavily influenced by films like La Belle et la Bete, the Seventh Seal, Nosferatu, Johnny Got His Gun, and Dracula amongst others, and the way the light works with the stories and the tension it brings to the scenes just brings me a certain joy. That tension I can face better than the tensions in real life. It thrills me.

To achieve a dark background like in The Drunkenness of Noah, I use either Cretacolor Negros, Kohinor Negros, Jerry's Jumbo blacks, or General's 9xxb pencils. The Cretacolor is my favorite as it has a bit of clay in it that makes it stick better, and it's a lot creamier than some of the other blacks. I lay down a layer of black gouache first and then use the pencil.

Being Slipshod, acrylic on paper, 24” x 18”

AAS: While your pencil drawings and etchings are dramatic in their use of light and shadow, you certainly don’t shy away from color. I think Being Slipshod is just a spectacular work with all the elements you have become known for. Would you talk about that piece?

DLF: You know, I don’t even know that model’s name. I do have several photos of him that I hope to use in the future in a documentary work. At the time, I was working extensively to photograph old school bikers. I’m not talking about what we’d describe as RUBS, or rich urban bikers who only go out on the weekends to pretend they’re bad guys. I’m talking about the real deal biker clubs who have parties in secret that I used to be invited to attend. Locals used to come out to party with the bikers, and it was usually the outsiders who caused any problems that came up, but that’s another story. The fellow in Being Slipshod had come to a party I was photographing along with a group of his friends, and I was attracted by them. They were local boys having fun, and they were all smashed and jolly, so I took several photos. I loved this fellow’s curly hair and his comic book shorts, so when I was looking for something that to me represented modern portraiture, which is often more about lifestyle than formal posing, I grabbed a photo of him as a reference. It doesn’t reveal his face, which makes him Everyman in a way. He’s someone anyone might know.

“I have a heart for stories and for making connections with others through story.”

AAS: You use a lot of models and you have spoken and written about that. Why is this important to you?

DLF: I have a heart for stories and for making connections with others through story. There was a time – and it’s a time I want to go back to when I have the time to do it, which means I have to be working full time as an artist and an educator to have the time – there was a time when I singled out people to photograph and talk to based on their stories of who they were. I learned that people are the stories they tell about themselves whether those stories are true or not, and sometimes it just doesn’t matter whether the stories are true because they get told so often they’re ingrained in the truth of who a person sees themselves to be. Whether that’s harmful or not, I don’t know, but I suppose I’ll find out eventually. I regret having not paid attention to more people’s stories when I was a child, and I regret not being able to hear more now because of my current place in life. It makes me sad that I’m not doing what I see as my calling in life, and that includes putting a whole picture together of my social and research goals as an artist.

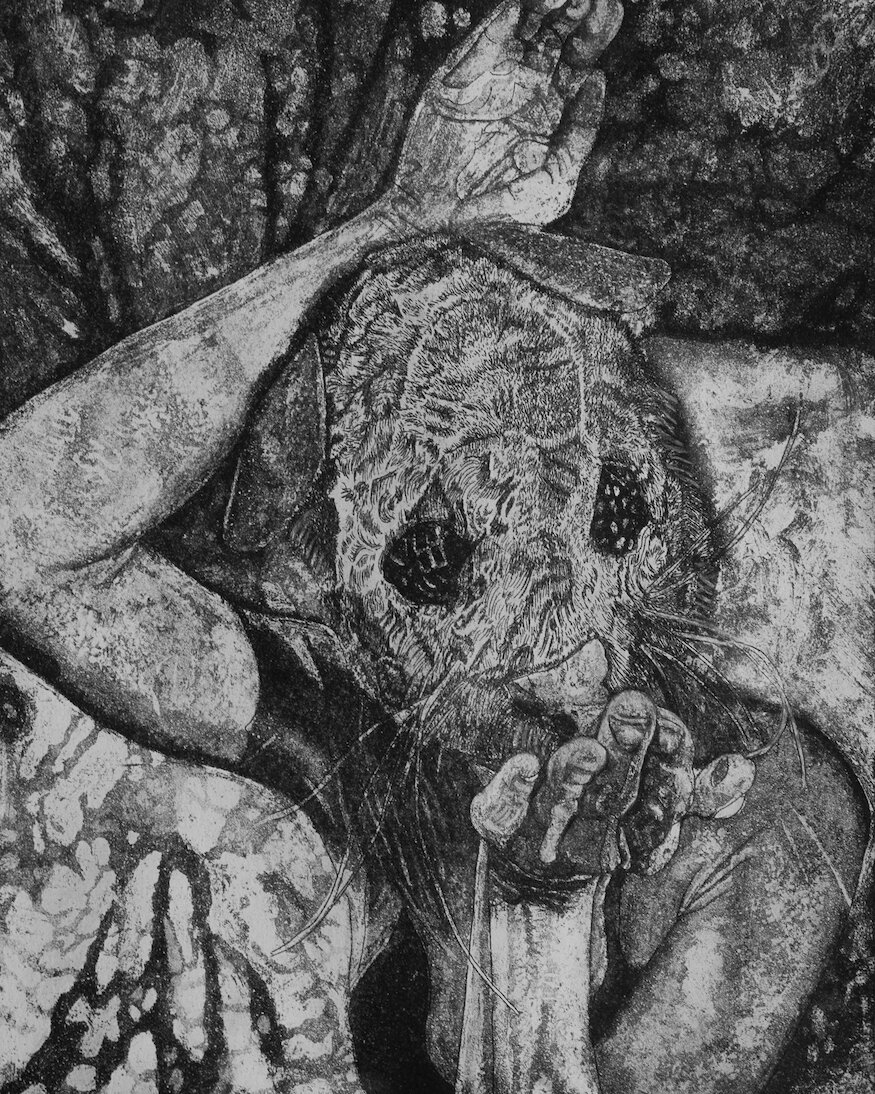

AAS: Rat King is another of your extraordinary works – in watercolor. What inspired that piece – I am almost afraid to ask?

DLF: Hahahaha. Once a student told me he liked my work because it’s creepy. Well, if it’s not creepy, it’s definitely dark. That’s something I can’t psychologically account for yet, but perhaps it’s because the creepy I see that can’t possibly be real is a whole lot better than the fear of reality I’ve carried all my life. In addition, I think mask making is an art, and I’m drawn to it, and if I had time, I would engage in it myself. It comes from my love of theater and film, I suppose. I collect them when I have the money, and the Rat King (or Mouse God as I sometimes call him) is one of my favorites. Did you know rats often form a living ball they can’t extricate themselves from and then end up ripping themselves to pieces? That bothers me to the nth degree. Anyway, the rat is something that most people – but not all – find disgusting. I want to unmask the disgusting. So, the Rat King will be around in several more works.

Rat King, watercolor, 22” x 30”

Pygmalion and Galatea, etching, 11” x 14”

AAS: Would you talk about your etching titled Pygmalion and Galatea and the characters you chose to interpret that mythology?

DLF: Mythology has delighted me since I fell in love with literary classics in the seventh grade. The story of Pygmalion, of being an artist capable of depicting your greatest love and then seeing it come to life, has been one of those impossible hopes I’ve let myself engage in. Pygmalion was alone, and he wanted someone to love. He made Galatea and loved her so much the gods let her come to life. I keep hoping for that. That’s probably one of the reasons I’m so frustrated with no longer being an educator and with not being a full-time artist. I feel like I’m no longer sharing, no longer contributing to life.

In the etching, Galatea is a statue from a cemetary and Pygmalion is my best friend Dustin Jackson. I use Dustin a lot because besides being extremely attractive, he’s very hip and modern, and I like that about him. I love the way he dresses. He stands out in a crowd, and he creates a certain atmosphere that conveys well in paintings.

The Smoke, graphite on paper, 30” x 22”

AAS: Your graphite drawing Smoke is not only a wonderful technical study, but it captures what I see as the distrust of the model – a ‘You really want to draw me? – Why?’ kind of a look.

DLF: The model is Wayne Summerhill, a marvelous sculptor friend of mine. He’s modeled for me off and on for years. Wayne is his own man, you know, he doesn’t give a damn what people think about him. He’s a Vietnam vet and an old school biker, and he’s probably taught me more about myself than anyone else I know. You might say meeting him was my awakening. I went from not even wanting to be in the same room with him because he was so “other” to my background as a died-in-the-wool Baptist to having him as one of my closest friends because I observed how giving he was to others. I’d been brought up to believe outward appearances were relevant to how a person acted and thought, and beginning with Wayne, I got a completely new education. When that drawing first went up on a gallery wall, a couple stopped me just before closing time that night and thanked me for putting “someone like them” up on a gallery wall for other people to see. That was it. That was the end of art for art’s sake for me. From then on, I’ve worked with people who have asked me the very question you asked: “You want to draw (photograph, paint) me? Why?”

AAS: You exhibit your work extensively around the state and around the country and you have earned many awards including an Honorable Mention from the Delta Exhibition in 2014. What do you enjoy about exhibitions and solo shows?

DLF: I’ve been told I’m primarily a ‘museum artist’. My work just fits the occasion, I think, because it’s not work someone can walk up to and understand all it once. It’s not just another pretty piece of Kitsch you want to hang in your kitchen or your toilet or that guests to your house can walk in and turn a blind eye to because it’s just there to decorate. I take a great deal of pride in being “chosen,” so to speak, because I haven’t been the chosen one in many other aspects of my life. Meeting people at exhibitions and having them speak good things about my work is the closest I often get to someone – pardon the Southern expression – loving on me. My work is me and I am my work. I am not the people I depict, but I am the work which depicts them, if that makes sense. Solo shows, well, I’ve done two in the past two years, which is exhausting and financially draining, but give me the opportunity to speak about my work. When I get to meet someone who understands what I’m saying and can engage with me in what I call “serious conversation” about art and culture, those brief times and encounters give me everything I need to keep going for a few more days. I keep hoping love will fall on me from love of my work. That’s a bad psychological predicament to be in, but it is what it is. By the way, I need people to BUY my work as well so I can afford to make more.

“To me, the best artists teach and do their best to support other artists of all types because they should know the struggle it takes to dedicate one’s life to the arts and how much criticism and how many financial and emotional and personal hurdles we all have to face.”

AAS: You are also very involved in film and especially the Hot Springs International Women’s Film Festival. Would you talk about that?

DLF: I was involved for a couple of years very heavily with the Hot Springs Arts and Film Institute, where I helped judge films, mount live performances, directed the Hot Springs Photography Festival, and helped put on film festivals, among them the Hot Springs International Film Festival that was started by Bill Volland. The entire institute is his baby, and at one time was housed at Central Theater in Hot Springs, which he has now sold. I was grateful to be able to work very closely with Bill, whose knowledge of film and filmmaking is extensive since he grew up in LA and worked in Hollywood. Central Theater became the place where I built my dreams and helped build other people’s dreams as a photographer. I lived in the bowels of that theater like the phantom of the opera. Bill taught me a good bit about the business and art of film, and the rest of what I know, which is not anywhere near complete, I got from meeting filmmakers and directors and producers and actors and composers who came in with the film festivals. I’m very sad not to be participating at the moment, but COVID helped kill more than people: it killed business and hearts and dreams. The festivals themselves didn’t die; they’re just having to take another form. The Women’s Film Festival will go on as it is a very important avenue for women in film, and, in fact, judging is going on at present. Bill also hosted the Hot Springs International Horror Film Festival, which included sci-fi, and it was one of my favorite festivals to work with because I’m a huge horror fan. It may sound silly, but the Institute and those festivals made me feel important because I was helping to provide training and performance and educational opportunities for other artists, both visual and performing. I spent one of the best portions of my life on stage and attended college as an art major on a vocal music scholarship, so the stage still calls me. To me, the best artists teach and do their best to support other artists of all types because they should know the struggle it takes to dedicate one’s life to the arts and how much criticism and how many financial and emotional and personal hurdles we all have to face. Giving collectively to the whole of society, which the arts strive to do – that’s my calling.