Interview with artist Sharon Killian

Sharon Killian is an artist living and working in Fayetteville, Arkansas. Her vibrant paintings are inspired by memories and experiences of growing up in Jamaica, Harlem, and her home on the edge of a hill on the White River in Fayetteville. Her work is in important private and corporate collections across the US. Sharon is anything but a reclusive artist. She is driven to promote diversity in the arts in Northwest Arkansas. Since 2014, she has served as president of the Northwest Arkansas African American Heritage Association, and in 2016 founded Art Ventures NW Arkansas, an arts and education non-profit, where she serves as board president. More of Sharon’s work can be found at Art Ventures NW and at her website. (profile photo by Jenn Terrell)

AAS: Sharon, I understand you were born in Kingston, Jamaica but lived most of your life in the New York/DC area before moving to Fayetteville. Would you talk about those times?

SK: I’m the eldest girl in my family and culturally and economically that meant for us that I was a caregiver. Punctuating a life filled with responsibility, there were indelible moments of mother daughter conversations outside in the perfect evening shade. I danced in the moonlight in my backyard as Bob Marley and the Wailers rocked around the corner. Over the years, my childhood memories of color, value, taste, and time have become a 4D reel that is simply a part of who I am. I emigrated from Kingston, Jamaica to New York City the year I turned 12 years old. I was happy in Harlem, glad to be with my parents again who had come to America three years before to save enough to make a home for us here. My new life was great, school was easy, girl gangs were not, and living in the ghetto was not a surprise. I became president of my high school class and the resident artist.

I always knew the conditions in the community were wrong but also planned. None of our corner stores were owned by Black people, there was no respect shown by the other immigrants behind thick bullet proof glass when we spent our money in the stores in our Harlem neighborhoods. Tourist busses drove through our blight and I was angry, like we all were.

I attended the University of Rochester in upstate New York where I earned degrees in art history and in painting. The best time was giving up pre-med and being the artist and art-thinker I always had been. In 1980 I moved to Washington DC, started a family and had a career in medical education. I managed Applicant and School Relations at the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) in DC for the first years of my children’s’ lives. Yes, I was responsible for thousands of applications to medical schools in the US and Canada. I began to teach art in 1991 and became very involved in mentoring K-12 students who attended less financially privileged institutions. I had an art filled life and a complete awareness of access and the lack of access with the intent to make a difference every day. In 2005, my husband and I retired to Fayetteville where we cared for his elderly parents and handled running the farm. During this time we planned and built our home. I painted a lot, sought out and found the Black community that was already quite dispersed and found the U of A School of Art, which became one of my personal haunts. I met the late Professor John Newman as I visited the classes and studios. We had great talks about DC and his next collaborative shows there.

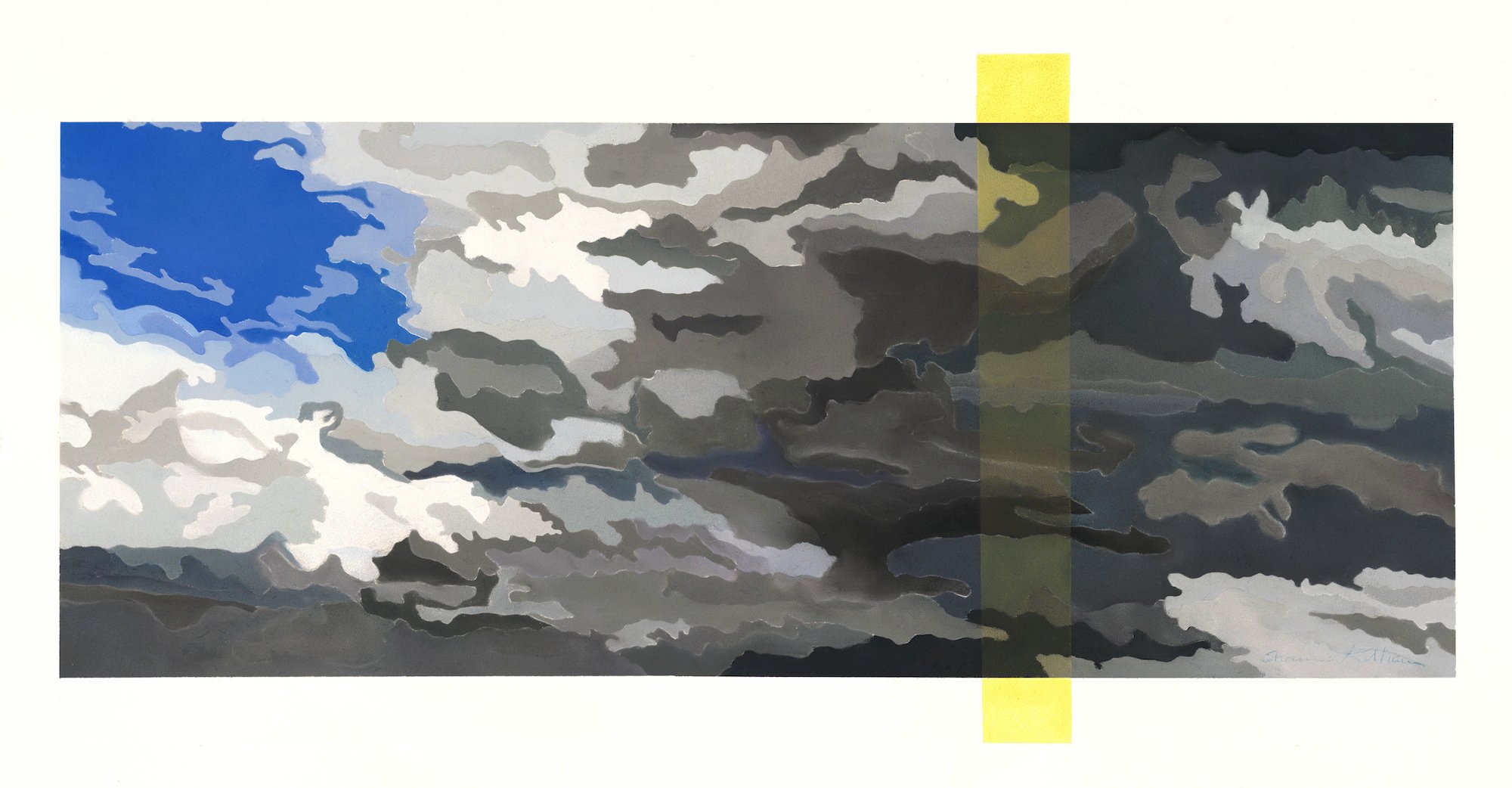

Fog in Wyman Valley, 17” x 53”, dry pastel on watercolor paper

AAS: When did you become interested in art and was teaching something you always wanted to do?

SK: I identify with my looking up at the dawn sky in Linstead, Jamaica as an eight year old doing chores as my acknowledgement that color, value, shape, space within the frame of my vision was a thing. My father wanted to be an architect but was made to work to send his younger brothers to school (at least one of those earned a Ph.D.). He became a cabinet maker, talked math when we were in his shop, then produced sweet lines that disappear because that’s what he wanted to happen with those numbers. I was always being told to turn off the lights and go to bed as I would paint late into the night downstairs. Of course, I was also asked to put up all my paintings on the walls in the house. But, I was an artist who thought the best path to make a decent living and take care of my folks was to become a doctor. Art was not the way to have a good financial future. No one was teaching me otherwise. I could see, too, that even with apparent success across the arts, certain of us would not reap financial benefits. So, I had no living artist role models really. As a high schooler, I haunted museums and galleries every day during the week (in between City Council and school council meetings, yearbook sessions, meeting up with news people, etc.) and my Saturdays were spent at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. I began to want to teach when I was in college. I thought everyone should be taught to know what I learned.

Blazing Sunset, 33” x 50”, dry pastel on watercolor paper

AAS: You describe yourself as a changemaker. Where did that drive come from?

SK: I don’t usually speak of myself this way, but I do work to create and have created positive change in culture through art and truth-telling. I believe my life in this body and my way of thinking about each person being a part of the whole created this drive in me. Every student, each person with whom I’ve planned and shared how we could improve a situation, will take a piece of the responsibility for change. And, when I see the impact of these interactions multiply, I am fueled to continue. Also, I am a dreamer of big dreams that come alive in my mind’s eye. Northwest Arkansas Black Heritage, the nonprofit organization Melba (Miki) Smith and I created in 2008, is a result of this dreaming. We are working to build a community where African American heritage, history, and contemporary life are valued as essential pieces of the fabric that is our country and I can see this beginning to happen. Intersectionality with art is everywhere in my life including my community volunteer activity that created Art Ventures, a non-profit art and education focused organization working to support artists through community engagement, collaborations, and cultural learnings through art.

AAS: You created a large work, You’re Killing Me, which is a commentary on social injustice. How are you hoping the viewer will react?

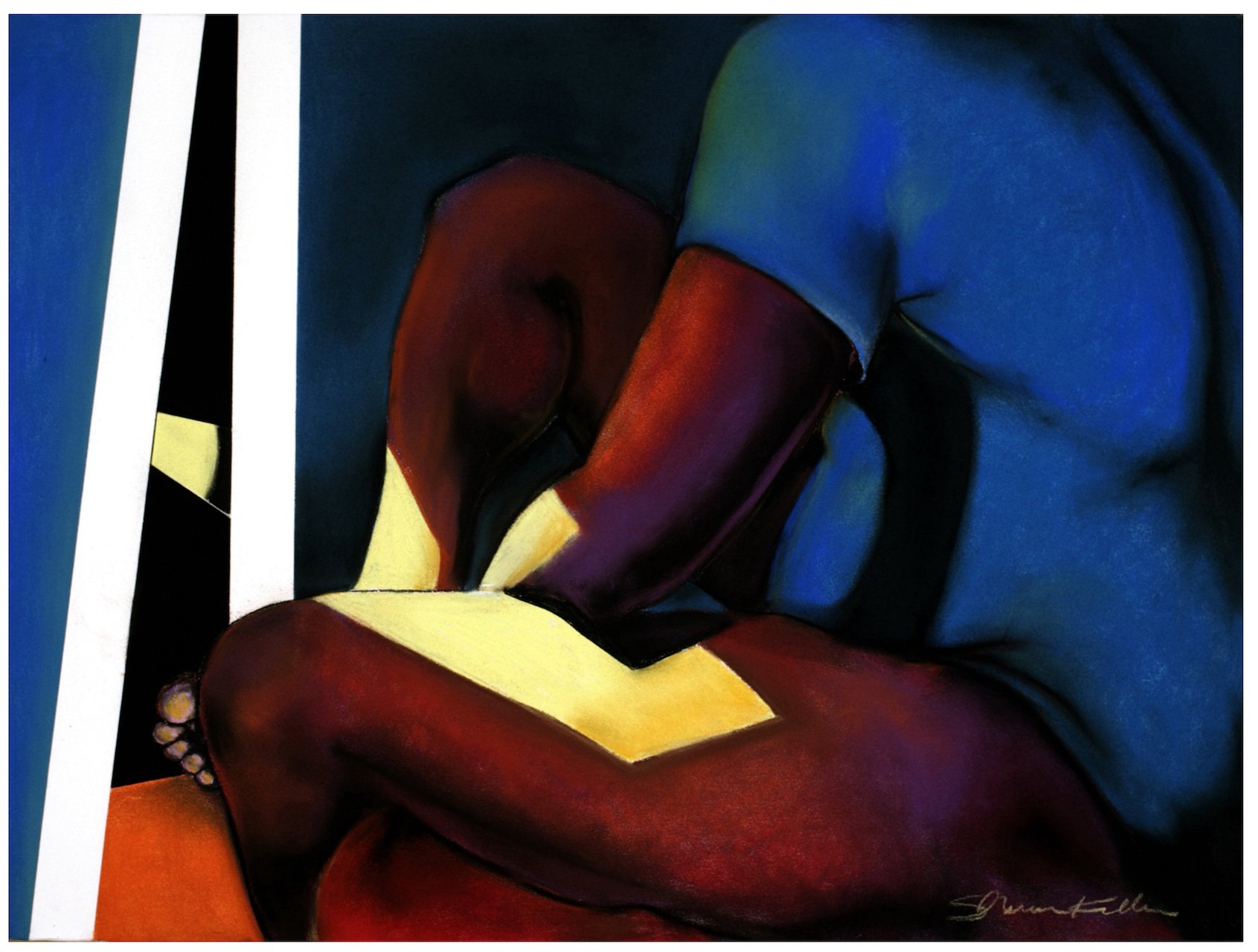

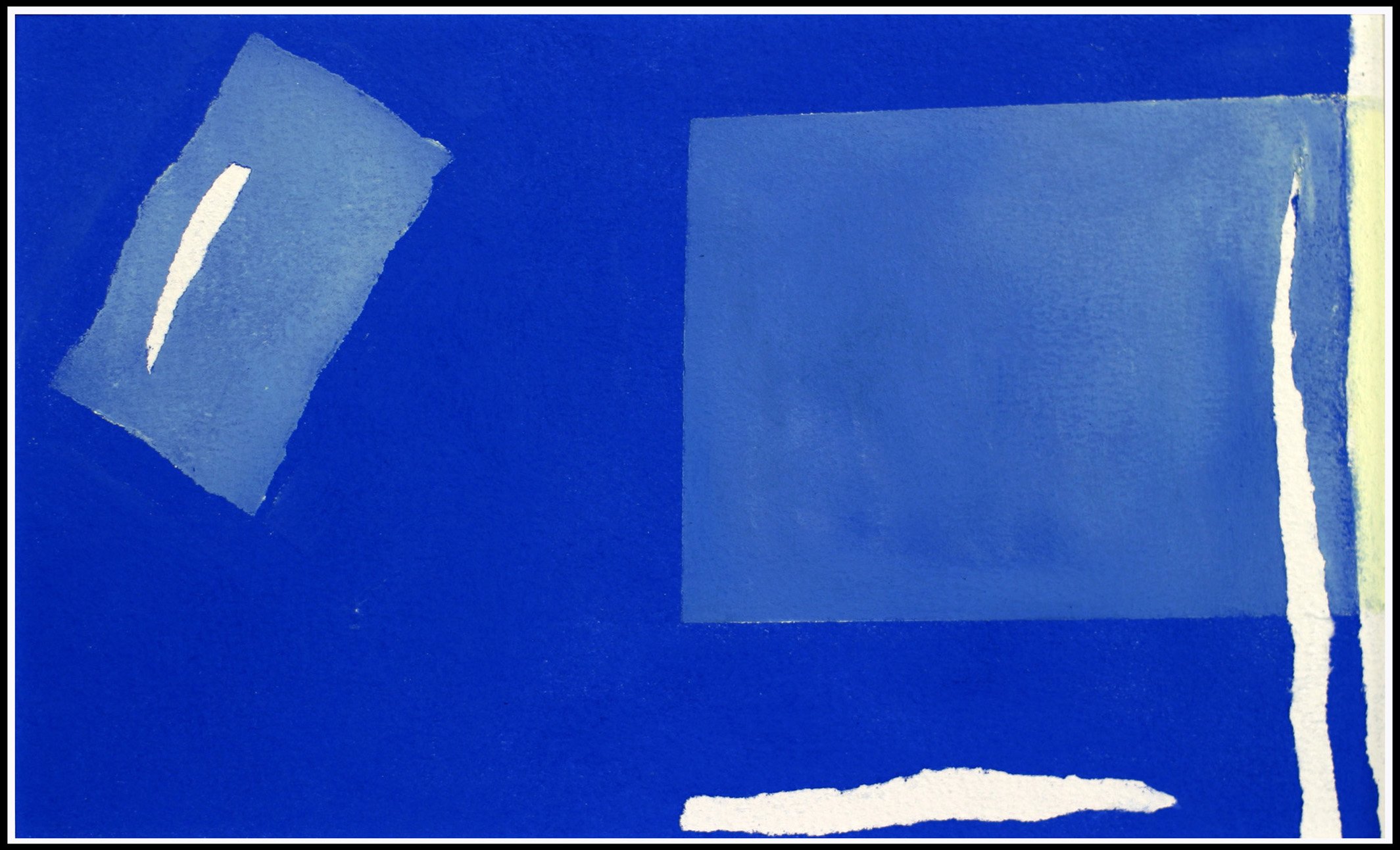

You’re Killing Me, 7’ x 4’, dry pastel and adhesive film on watercolor paper

SK: You’re Killing Me is the only piece in a series of works that is in my heart and head to be continued as I make studio space and time for myself. The reason I am so sure of this as a next step is that for all the years I have been alive I hoped and worked to change the world one bit at a time by giving all I can to it. And yet, Black people are still being lynched in the same way we have always been – in the open, with impunity, and filmed! The victim could very well be my son or daughter--- still.

The painting is in dry pastel pushed into watercolor paper then layered with the skin of the abstract shapes created to mask the colors representing the child. The upright form of the child is positioned at the very bottom of the frame in a horizontal position. The smile is demure, eyes innocent, and the palm of the hand is open and facing the viewer. The childish wave is “hands up” don’t shoot in its context with a pair of “hands up” directly above the horizontal form and their skins repeat throughout the composition. Upon close observation, blood red is upon the body, behind and on the hands along with police blue.

In response to this piece the viewer turns their head sideways to the left to see the child’s face. As I watch, their smile about the beauty in the smile and the softness in the child’s hands fades.

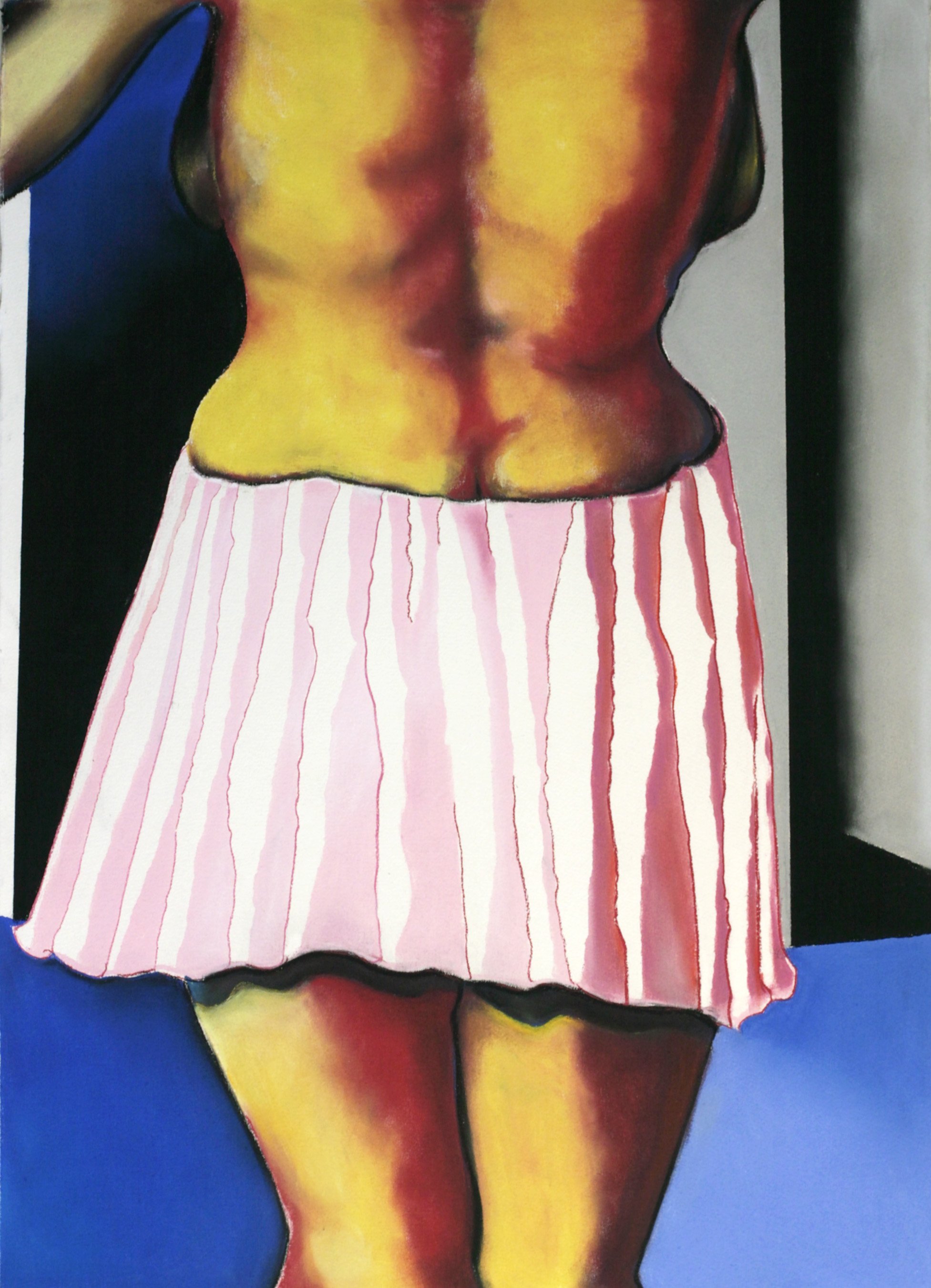

AAS: Your abstracted landscapes are often bold and explosive. I think Circles Around Me is a good example of that. Do you feel energized while you are painting?

SK: I am absolutely energized as I paint. The ridiculousness of sunsets, the inaccessibility of it no matter how hard you stare, pretty much pushes me to recreate the feeling I have about how small my humanity is in comparison. Circles Around Me is a scene from my west facing porch looking through the shapes of a director’s chair and through steel railing toward the sunset. Significant edges of clouds are hard edged and totally incongruous to the softness of it in our imaginations.

Circles Around Me, 33” x 50”, dry pastel on watercolor paper

“I want to show the viewer how everything can be an abstraction, sometimes a hard-edged one in the softness of a cloud or the turn of flesh.”

AAS: Would you talk about your painting technique?

SK: Everything is an abstraction and when I paint with dry pastel, I am deliberate about defining many forms with hard edged, finite shapes. I want to tell nature, tell my sight that I understand. I want to show the viewer how everything can be an abstraction, sometimes a hard-edged one in the softness of a cloud or the turn of flesh. I have always loved to use a blade and I get extra pleasure hand-cutting the shapes I see. I cut the shapes of color into as many values as are relevant, scrape pastel into dust and mix the colors directly onto the paper with my fingers. No other tool works to lay the color with the texture I need. Also, every color is mixed with another to get the vibrancy hue I desire.

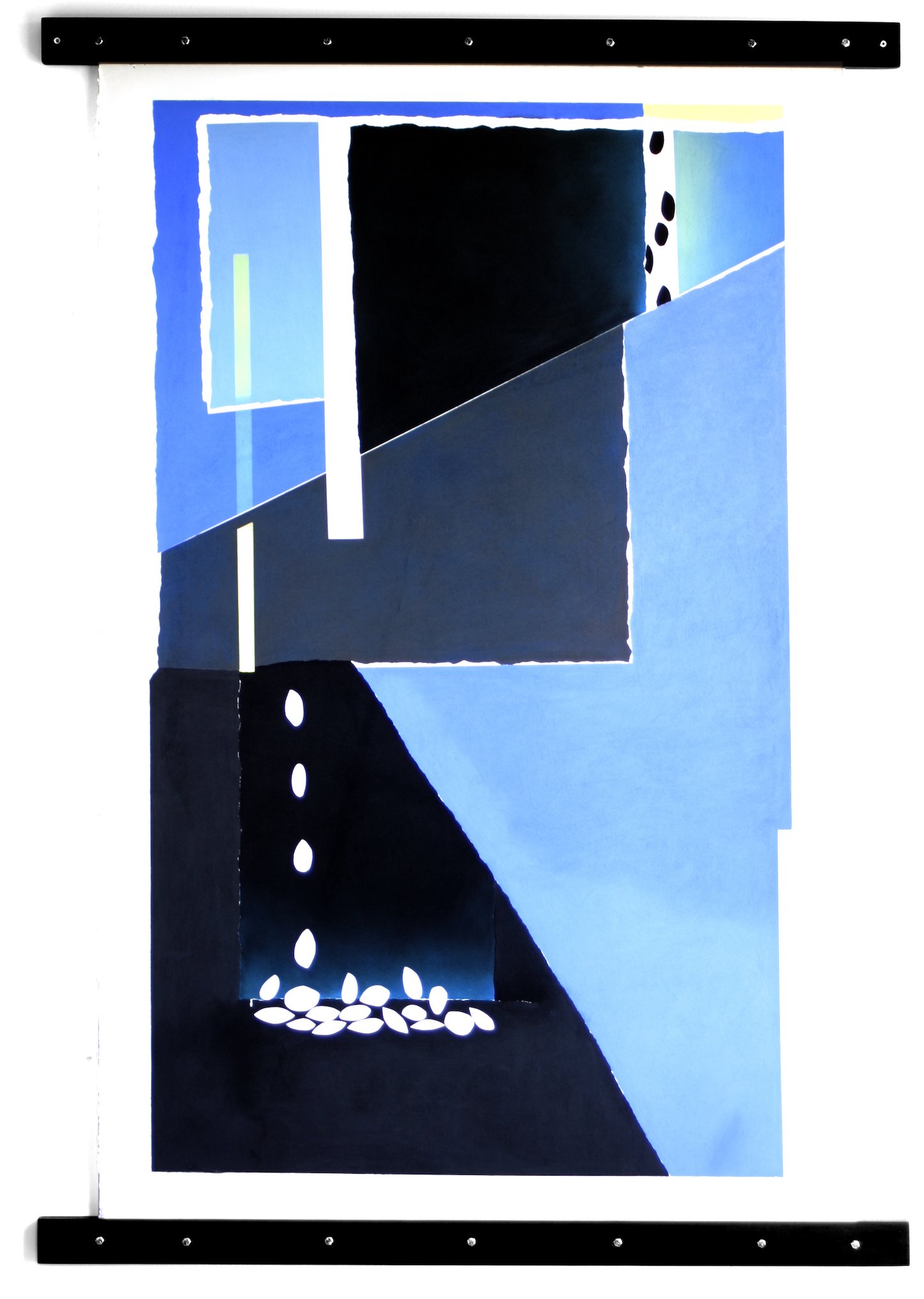

Petals, 30” x 22”, dry pastel on watercolor paper

AAS: Your painting Petals has a lot of movement. Would you talk about that piece? And when you begin a new work that is more abstract, do you have colors or shapes already in mind?

SK: Petals was inspired by the ancient American elm tree in my husband’s back yard on College Avenue in Fayetteville. I enjoyed cutting the serrated edge detail of the leaf in the bottom center with an X-ACTO knife. The work was developed beginning with the leaf and that led to the selection of the shape and size and position of the format. Each part of it was created as I developed the composition based upon principles that attracted me at the time. As in a series, which this was not part of, I set a series of parameters and push the envelope from one to the next until I exhaust myself or the concept using those parameters.

AAS: You’ve done some wonderful figurative work. Two of your portraits, Daughter and Son, are strong and powerful, just like I suspect your daughter and son are.

SK: My approach to painting portraits is the same as with abstractions. Everything is a shape a piece of color without preconceived expectation. I try to separate my emotion from the execution of the image. In the interim as the work progresses, I enjoy how much the emotion is generated by the countenance, the intrinsic value of the person’s character that emanates through their own form.

My daughter and son are both powerful people and it’s great that you can recognize that in these paintings. Their power begins for me as two Black American people who no matter how intelligent, funny, thoughtful and loving, have to navigate every moment of their lives with more than the average amount of uncertainty of surviving each day. That is powerful. I am really happy that part of their power is loving each other too. Our son is a jewelry maker here in Northwest Arkansas and our daughter is communications director of an essential nonprofit organization in New York City.

Daughter, 30” x 22”, dry pastel on watercolor paper

Son, 30” x 22”, dry pastel on watercolor paper

AAS: A few years ago, you had back surgery. How did that impact your art practice?

SK: The surgery had to be done. There is less pain. My head hasn’t fallen off! It has impacted my practice enough that although I resist, it is impractical to continue to cut my own friskets. I’ll at least still use my own line to machine cut. And, there are other adjustments that I have made such as using a neck brace, taking more time to dance during work as I listen to my favorite music, and not working for straight eight hour periods.

AAS: Tell me more about Art Ventures in Fayetteville. What is its mission?

SK: Art Ventures is the embodiment of the accessibility to artists and learners that I wanted for myself as a youngster and as a professional artist looking to launch my art life. Knowing that this was possible to achieve, a village has been created to help “…promote the visual arts by actively collaborating with the community, supporting artists working to the highest standards, encouraging education and public engagement in the arts, and being accessible to underrepresented communities.” With the help of a Windgate Foundation grant we were able to hire our executive director in June 2021. Lakeisha Edwards comes from a social work background and is perfectly suited to bring people together, creating community and change through art.

AAS: How do you describe the art scene in NWA?

SK: The art scene has changed in NWA in a big way since I arrived in 2005. When I was in DC, the Fisk Collection was at the Corcoran Gallery and I learned there were discussions going on about how to care for it and keep the HBCU, Fisk, the owner of the collection. I didn’t know then that Alice Walton was involved but she was. I was happy to be faced with the special exhibition of the collection very soon after Crystal Bridges opened in NWA. I thank Alice Walton for my not having to travel out of town to see art. Like most of us though, I am looking forward to being able to choose the option to freely travel again. Creative Arkansas Community Hub & Exchange (CACHE) has been a great resource for individual artists and for art groups in our region, especially over this three year pandemic period. I think progress in the arts and in diversity has made some advancement. I want to publicly thank Steuart Walton and the Walton Family Foundation for the cash award aligned with the Creative Impact Award that I received for 2021 though I’ve never expected anything in return. Martin Miller slipped one in on me with that nomination and I’m honored to have been selected by the committee.

AAS: What advice do you have for artists just starting out or who are thinking about changing the direction of their art?

SK: It is good to find an artist that you trust to talk to about where you want to go with your work so that you have a relevant sounding board. My thinking on this is perhaps old school, tinged with the “art for art’s sake” concept, which means that the decision to change direction has to come from the center of your art place and makes sense to you in your own element. The change is inevitable and good if it comes from that place.

Ice and Fire Sky, 17” x 56”, dry pastel on watercolor paper