Interview with artist Rex DeLoney

Rex DeLoney is an artist and educator living in Little Rock. He earned a BA in Commercial Art from the University of Central Arkansas and an MA in Education from Central Washington University in Ellensburg, Washington. Rex has been teaching art to middle and high school students for over 30 years, the first 14 of those in Washington state. For the last 17 years he has taught at Central High School in Little Rock, where he serves as Fine Arts Department Chair. Rex’s paintings are bold, both in color and statement. More of his work can be found at Hearne Fine Art in Little Rock and at his website rexdeloney.com. (profile photo by Joshua Asante)

AAS: Rex, I understand you were born in North Little. Have you lived all of your life in the Little Rock/North Little area?

RD: I am the youngest child, of seven children born to the late Elder William H. DeLoney Jr. and Hazel B. DeLoney. My Dad was a barber and a pastor and my mom taught in the NLR School district for 28 years. I have four brothers (my eldest brother William Henry III, passed in 1986) and two sisters. I was educated in the North Little Rock School District. I graduated from North Little Rock Northeast in 1983. I attended the University of Central Arkansas, where I received a BA degree in Commercial Art in 1988. After working a year at Pyramid Art Gallery in Little Rock, I moved to the Pacific Northwest (Yakima, Washington). The move was prompted by a desire to build a career as a freelance sports illustrator. I began working as a paraprofessional at a local high school in Yakima. One of the art teachers at the high school invited me to share my artwork with his class. After the presentation he told me that I should consider becoming an art teacher, because it was the best job that an artist could have! I guess he was right, looking back thirty years ago. I became certified to teach in a special program within the district and in 2000 received an MA in Education from Central Washington University. After living and working in Washington for 14 years I moved back to Arkansas in 2004. I worked one year at Jacksonville Junior High. In 2005, I was hired to teach art at Little Rock Central. I serve as the Fine Arts Department chair as well as teaching painting and AP Art and Design. I am currently in my 17th year at Little Rock Central. I am married to Barbara Terri DeLoney, we met at Central and were married in 2011. I have one daughter that stepped into my life when I married her mom. We are blessed with five grandsons ranging from ages 9 years to 16 years old.

AAS: Did you have role models growing up who were artists?

RD: My family was very supportive of my dreams of being an artist at an early age. I began drawing before I was in the first grade! Our home was filled with all types of books on history and art. I have fond memories of creating drawings from my older brother's art books as a young child. All of my brothers were very talented artists. My brothers Timothy, Kent and Wayne were really good artists and my role models. We were PK’s (preacher's kids), so we were always competing in church youth art competitions while growing up. I looked up to my brothers, so I guess I naturally followed in their footsteps. I idolized my eldest brother, William. He was an outstanding basketball player at Northeast High in the early 70’s. Henry would bring me Sports Illustrated magazines and notebook paper so I could draw images from them and that is where my desire to become a sports illustrator was born.

My brother Kent, whom I am closest to in age (3 years) was the artistic Elijah to my Elisha. Kent was an outstanding artist in high school and college. He was that student in high school that was always asked to do paid commissions and win awards. He left a very large shadow to fill following in his footsteps. My parents, especially my mother, who is 90 years old, supported and displayed my artistic talents. I would often create drawings for her bible lessons or draw pictures on her chalkboard during open house night when she taught at Poplar Street Junior High. Recently she gifted me a building to have my own gallery and studio in the neighborhood where I grew up. My art has always been intertwined with my faith. My earliest memory of my artistic skills goes back to my childhood pastor, Elder L.C. Dade, preaching a sermon about a chalk drawing I did in Sunday School, I believe I was 8-10 years old. The picture was of a large hand holding the world and his sermon was He’s got the whole world in his hand. As a child , I looked up to a local artist that worked at our neighborhood community center, Greg “Doc” Gaines. I watched him paint countless murals as a child. He was my J.J. Evans, back in the day [from the Good Times TV Sitcom]. I recently saw Doc out painting a mural. I had the opportunity to tell him that I watched him paint murals and now I have painted twelve murals.

AAS: You have been an art teacher for a long time. What do you most enjoy about teaching?

Rex with students at Central High School.

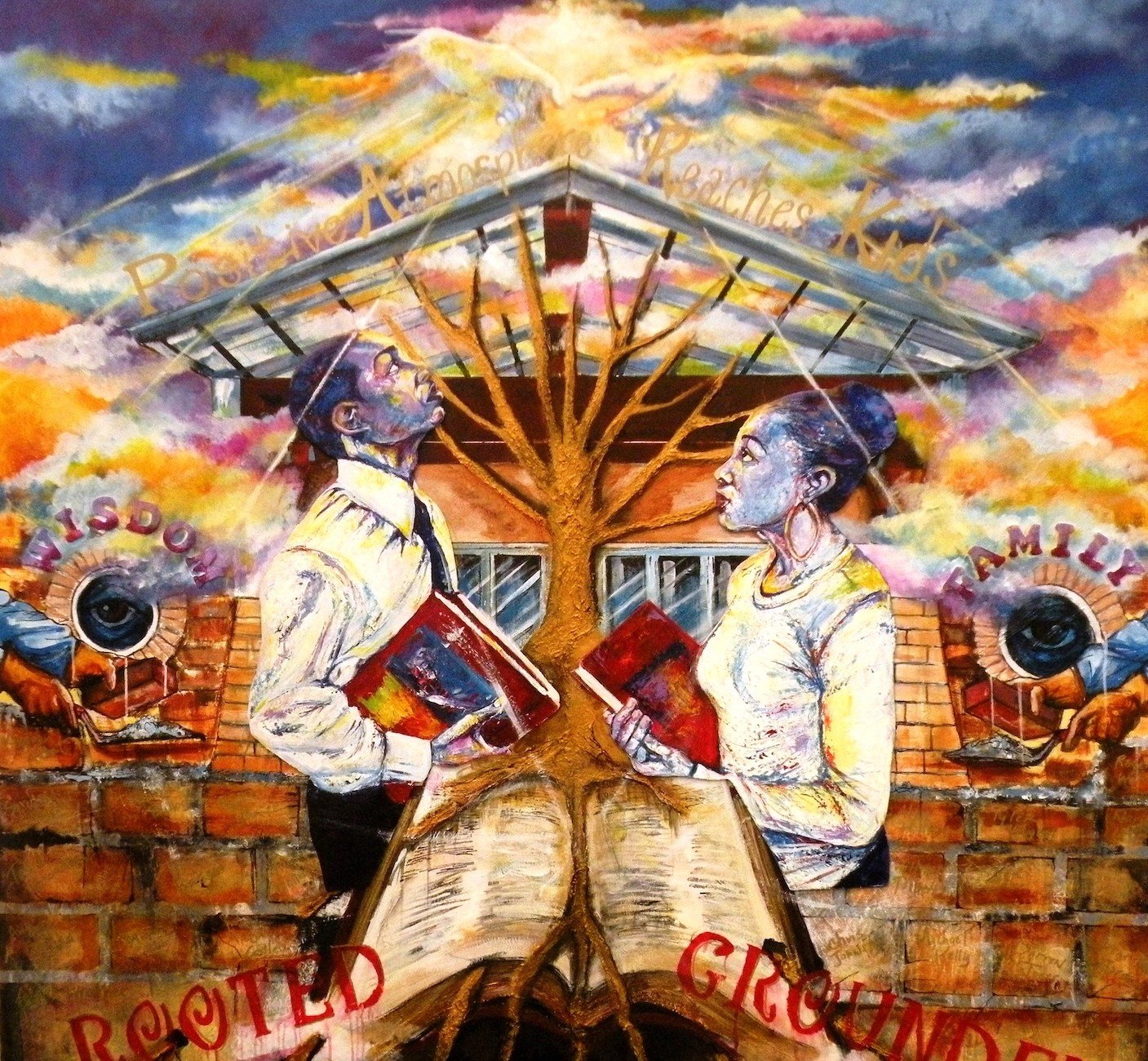

RD: I have taught art for thirty years, but as I tell my students all the time; I teach life, art is just the vehicle I use! I most enjoy building true relationships with my students that foster creativity, confidence, and courage with their art and in their lives. Another enjoyable aspect of teaching for me is that I get to share my passion and visual voice through my pedagogy and artwork to inspire positive learning experiences that will have a lasting impact on society.

AAS: Your artwork is often very spiritual. I am thinking here of Why Are We the Shadow and Not the Great Tree and your use of symbolism.

Why Are We Are the Shadow and Not the Great Tree, 30” x 20”, mixed media on paper

RD: I believe my artistic talent is gifted from God; therefore, spirituality plays a major role in all of my work. Why Are We the Shadow and Not the Great Tree is steeped in symbolism to provoke the viewer to ponder the question in the title. I wanted to look at how black girls are often mistakenly negatively perceived in some public settings. Abraham Lincoln said (paraphrased) “Character is like a tree and reputation is like a shadow, the shadow is what we think of it; the tree is the real thing.” Many of these young black princesses are judged on their reputations before their character has a chance to develop or shine brightly. I asked one of my students to pose for the painting. The two silhouettes face each other and the stenciled tree becomes part of the young woman’s posture. Her inquisitive eyes and a non-threatening posture speak volumes to misconceived perceptions.

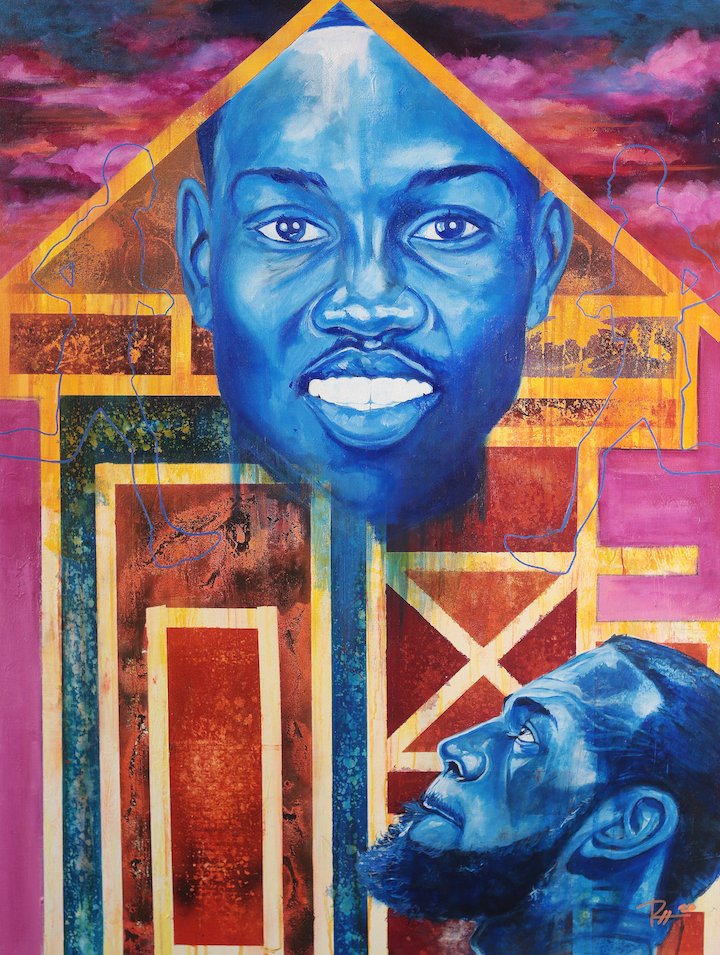

AAS: I like the way you used color in We, Too, Sing America and Not My Anthem. Would you comment on your use of color to enhance and even emphasize the message?

RD: My palette is often driven to my favorite complementary color scheme of blue and orange. The blue hues are used to symbolize a grounded tranquility and orange symbolizes an optimistic determination.

We, Too, Sing, America is my twentieth century visual interpretation of Langston Hughes’ poem I, Too. The poem was written magnifying the Jim Crow era treatment of African Americans being sent to the kitchen backdoors of America, because they were not equal to their white counterparts. While the poem uses visually thick phrases like “the darker brother”, I chose to portray three former Washington students in the most patriotic colors available, red, white and blue. The symbolism is that while African Americans were treated as second- or third-class citizens then, now they (We, Too,) have the same rights as others and a place at the table.

We, Too, Sing America, 23” x 40”, acrylic on paper

Not My Anthem, 38” x 42”, mixed media on paper

Not My Anthem is the story about Wayne Collett and Vince Stephens in the 1972 Munich Olympic games. After the much-criticized 1968 black power salutes by Tommie Smith and John Carlos, Collett and Stephens were faced with some of the same unfair treatment by coaches and racial inequality in America. The athletes were warned against making any protest on the winner’s stand, so instead they looked disinterested, hands on their hips, talking and laughing. The two men received a lifetime ban for their conduct. I created a colorful collaged background on paper with random words and phrases to symbolize the commotion and turmoil that existed during the games. I decided to portray Collett and Stephens in a neutral color to symbolize their state of mind while creating a greater contrast in the composition.

AAS: Your use of abstract realism and mixed media has created some powerful images. I am thinking of Rosa Parks After Giovanni’s Poem Rosa Parks. What is the story behind that piece?

Rosa Parks After Giovanni’s Poem Rosa Parks, 16” x 16”, mixed media on paper

RD: I actually had the pleasure of meeting and talking with Mrs. Rosa Parks while I lived in Yakima! One of the most memorable events in my life. I actually touched history. The piece was part of an exhibit at Pinnacle Fine Arts in 2018 called The Brotherhood of Color that focused on The Pullman Porters. Giovanni’s poem is paying tribute to the men that were responsible for securing the transportation of so many pivotal figures in African American History. I wanted to tell a mixed media story that moved across the canvas like the trains moved across the country carrying the likes of Thurgood Marshall, Rosa Parks, and Emmett Till. I used collage and transfer techniques, as well as some acrylic painting. The painting has an overall abstract feel because of the layers of overlapping images layered with tissue paper.

AAS: Another tribute piece and one about poetry is of Gwendolyn Brooks and her poem We Real Cool. Does her poetry have a special meaning to you?

We Real Cool, 16” x 20”, mixed media on paper

RD: I use appropriation in some of my work. My Mom taught History and Civics so we had a library full of African American History books that were filled with black and white photos of notable African American writers, politicians, actors, writers, etc. I have always preferred working from black and white photos to create my own colorful compositions. We Real Cool, is an example of that. And, by the way, it won the Purchase Award for the 2018 Arkansas Arts Council Small Works On Paper. Ms. Brooks’ poem reminds me of the cool slang that was often used in movies and television shows during the early 70’s. One of my main goals in my paintings is to provoke a nostalgic feeling for the viewer with the use of color.

And yes, I love poetry, especially poetry by African Americans poets that chronicle history and reflect the African American culture. I believe I stated earlier that I love creating from visually thick words and phrases. I read poems and God paints pictures in my mind.

AAS: One of my favorite pieces of yours is A Quilt for Rosie Lee. I love the way you tell her story through mimicking her art form. Why did you want to create that piece?

RD: I had so much fun creating A Quilt for Rosie Lee. First, it was commissioned by a former colleague that I taught with in Yakima Washington, Jim Bodeen. Jim commissioned the painting for his wife Karen, a quilter in her own right. I extensively researched the life of Rosie Lee Tompkins, from her humble beginnings in Gould, Arkansas to her ascension as a quilt (piecing) master. I wanted to tell her story by creating a Faith Ringgold type quilted painting that would leave Jim and Karen finding new nuggets every time they walked by it in their home. I used fabric, collage, photo transfers, and painting to create a smorgasbord of color, lines, textures, shapes, and forms. Jim was an English teacher and he had a bulletin board with all the papers his students had written over the years layered upon each other. He would tell me to listen as he would push the thick board full of written papers as they would contract and expand, “it breathes” he would say. I wanted to create a painting for him and Karen that would breathe! It is my most detailed work to date. I spent several months completing the painting.

A Quilt for Rosie Lee, 22” x 30”, mixed media on paper

Live Catfish, 48” x 24”, mixed media on paper

AAS: Another of my favorites is Live Catfish. Your use of color is magical.

RD: Live Catfish is a piece from my Colored Porches exhibit held at Hearne Fine Art in Little Rock. The exhibition had 20 of my paintings, which I used to examine how the back and mostly front porches in African American culture have long been a meeting place to chronicle history, share stories, and take photos of family events. Live Catfish is an acrylic painting I did from a photo by the American photographer Marion Post Wolcott. I used aluminum foil and modeling paste to build the texture of the cabin in the background. I used green to paint the figure to symbolize serenity and the oneness with nature.

AAS: Many of your pieces speak to social issues. Do you encourage your students to use art to raise awareness of social issues?

RD: Yes, I do. I always stress to my students to find and use their visual voice in their artwork to bring about change or to shine a light on injustice. I have a couple of assignments that I intentionally assign to activate their minds towards awareness. The climate that we have been living in during this pandemic has really channeled the minds of young people today with an unrivaled passion to challenge injustices anywhere.

AAS: What are your art students most concerned about?

Artist As The Teacher – self portrait, 36” x 48”, acrylic on canvas, Honorable Mention at the 55th Delta Exhibition

RD: I believe my students are most concerned with what role they will play in future as citizens of the world. They have such strong beliefs and conquerable dreams. As an educator, I not only have a pulse on future artists, but on future doctors, lawyers, teachers, and politicians. I have had the pleasure of looking into the canvas of the future and I’ve seen the palette that is being used. I think they will create masterpieces!